Interview with Nisa Ari, winner of the 2017 Rhonda A. Saad prize

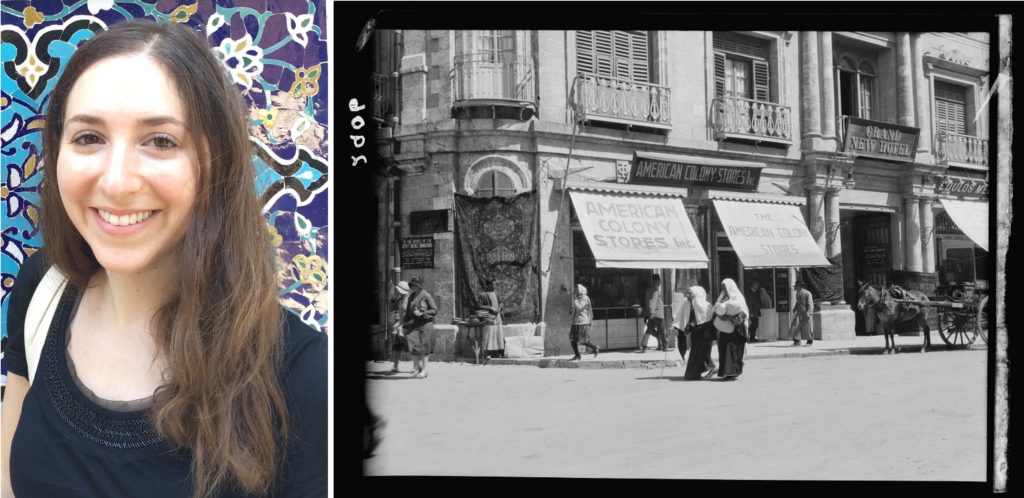

Left: Portrait of Nisa Ari; right: “American Colony Stores in the Grand New Hotel, The Old City, Jerusalem,” nitrate negative, 4 x 5 in, c. 1920-1933. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Matson (G. Eric and Edith) Photograph Collection, LC-M33-2906. Image in public domain.

In 2017 the Committee for the Rhonda A. Saad Prize for Best Paper in Modern and Contemporary Arab Art chose to award Nisa Ari for her submission, “Painting After Photography: Nicola Saig, the American Colony Photo Department and the Art of the Copy in Palestine’s Early Twentieth Century Art World.” A PhD candidate in the History, Theory and Criticism of Art and Architecture Program at MIT’s School of Architecture, Ari is currently completing a dissertation on the development of the visual arts in Palestine during the late Ottoman period and the British Mandate. To better understand the work done by winners of the Rhonda A. Saad Prize, from this year onward AMCA conducts interviews with the winners, providing a more in-depth look into the research themes and methodologies of those who win the award. The following interview, which is the first in our Rhonda A. Saad Prize interview series, was conducted by Pamela Karimi on behalf of AMCA in April 2017:

§

AMCA: How did you come to your research topic on the development of the visual arts in Palestine between 1876-1948?

NA: The idea for the topic was born out of my curiosity for what could be discovered in regard to the visual arts in Palestine when the labels of “Palestinian art” and “Israeli art”—both concepts largely unspoken before 1948—were taken out of the equation. What did it mean to be an artist in Palestine during this period? Who was considered an artist? What were the institutions encouraging the production, display, and circulation of art and who was granted their services? How were new methods of artistic practice being formulated and by whom? I wanted to investigate how the notoriously complex set of forces impacting Palestine in the early twentieth century played a determining role in both the formation and separation of these two artistic fields, while also making space for the many immigrant practitioners and international agents who are also a part of this story. Just as scholarship has atomized the cultural categories of Jewish (later, “Israeli”) and Muslim and Christian Arab (later, “Palestinian”) art prior to 1948, so too have discussions about the many foreign artists in Palestine during this period (British, American, Russian, etc.) been mostly siphoned off and addressed separately, owing to operative politics that have necessitated the rigidity of these two canons.

§

AMCA: Your awarded paper, a segment of your dissertation, focuses on the work of Nicola Saig—a Christian Arab who was influenced by the traditions of Russian Orthodox icon painting. The artist’s background and influences speaks to the oft-forgotten cosmopolitan nature of Middle Eastern art. How does your study of Saig help us re-consider Middle Eastern art and its very many dynamic dimensions?

NA: Palestine, like many other places in the Middle East, was host to a myriad of cultures, but it has a unique history as a site of pilgrimage for the world’s three major religions. Saig’s icon painting techniques were not purely learned from foreign missionary artists, nor solely gleaned from traditions among Levantine iconographers that spanned centuries. Merely gazing at the face of a saint he painted reveals the pluralistic atmosphere of his artistic upbringing, combating narrow or monolithic ideas what Middle Eastern art looks like or how it is produced. I was especially interested to learn how over the course of his career Saig showed his practice to be porous and he exhibited a sharp mind for participating in and capitalizing on trends in Jerusalem’s art market. As I looked closely at how Saig employed the ubiquitous, hand-painted photographs and postcards produced by the American Colony Photo Department for his first experiments with genre painting, I was able to better understand how transformations in artistic practice were engendered by the rapidly changing communal and political fabric of late Ottoman Palestine. Such a study relieves him, temporarily, of his posthumous label as a veritable ‘grandfather’ of modern Palestinian art, and assess the cunning nature of his talent in his own time.

§

AMCA: What has been your approach in studying this topic?

NA: Ever since working as an administrator in contemporary art centers prior to starting my PhD, I have been fascinated with how institutions and their social networks mediate artistic form. In locating and studying art objects, periodicals, and archival papers, I pay special attention to traces of governmental, quasi-governmental, and non-governmental organizations that emerge in artists’ artworks and personal papers. Following these leads has resulted in some of my most intriguing findings so far.

§

AMCA: How is your study different from the work done so far by other art historians?

NA: My study is indebted to the few book-length studies of Palestinian art, for example Kamal Boullata’s analysis of changing pictorial expression among artists before 1948—primarily through the media of icon painting, photography, and traditional embroidery. However, a considered institutional history of the local and foreign missions in Palestine, which fostered these changes and aided in the creation of spaces for exhibition, remains to be produced. To address this lacuna, I draw on scholarship considering culture’s utility to politics—such as in the related fields of architecture and archaeology. My investigation into the processes and agents driving the institutionalization of the visual arts in Palestine shares and expands upon this scholarship’s interest in institutional interventions in nation building and cultural practice, and the agency of the Palestinian people therein. Put another way, I’m interested in how “art worlds” were formulated within this turbulent, but culturally vibrant period.

§

AMCA: What have been the challenges and rewards of undertaking this research so far?

NA: When I began this research I was warned that there might appear to be a relative dearth of artworks produced by Arab Palestinians during the period I was studying. I have found this to be far from the case. It is my understanding that Rhonda Saad’s dissertation research was pioneering on this front as well. It has been incredibly rewarding to collaborate with other scholars who are often doing the difficult work of locating artworks, talking to the descendants of artists, and collecting artworks. It feels great to be a part of a field that is actively expanding. Journeying to sites in Bethlehem, Ramallah, Tel Aviv, Jerusalem and beyond has forced me into contact with a diverse array of individual perspectives and encouraged me to become a better listener and draw more nuanced conclusions about the historical materials I am encountering.

§

AMCA: As you know, this award was initiated in the memory of our dear friend, Rhonda Saad, a young Palestinian-American scholar who was very passionate about Palestinian art and visual culture. Could you tell us why discussions surrounding Palestinian art or modern Arab art are important today?

NA: Palestinian art and modern Arab art, just like the concepts of Palestine, the Middle East, or Islamic civilization, are overwhelmingly predicated by the notions of difference and distance in U.S. news media, as well as in many pockets of the art historical discipline. By questioning the validity of using Euro-American theoretical frameworks to interpret cultural and artistic practices elsewhere, and in searching for a more historically responsible and precise vocabulary to narrate these traditions and shifts, I hope to help dissipate ingrained and antiquated perceptions about Palestine specifically and Arab cultures generally.