Read AMCA’s interview with this year’s 2019 Saad Prize winner, Lara Ayad on her submission, “Homegrown Heroes: Peasant Masculinity and Nation-Building in the Paintings of Aly Kamel el-Deeb.”

Paper Abstract

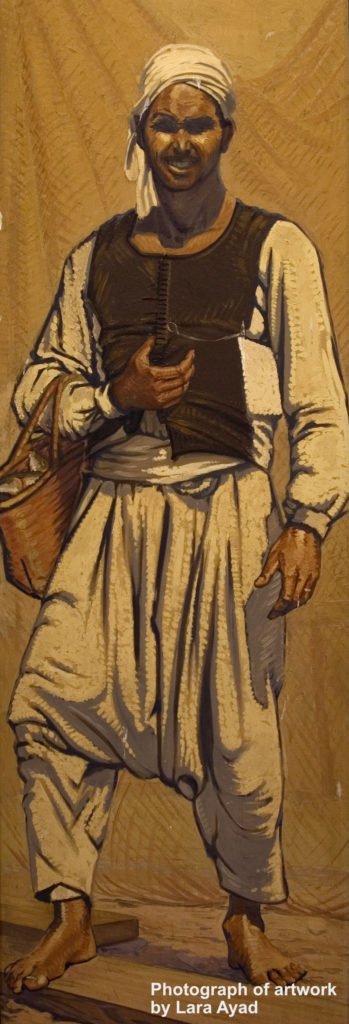

This essay examines a series of four paintings created between 1934 and 1937 by the Egyptian artist Aly Kamel el-Deeb (1909-1997) for the Agricultural Museum. I argue that the male peasant subjects of his painted series, which he left untitled, functioned as heroic members of the Egyptian national community. Central to formulating the image of a national community in Egypt between the World Wars were concepts of nation-building and their intimate ties with ideas of masculinity. My essay situates el-Deeb’s untitled series in contemporary debates among nationalists and artists about the role of peasant men in achieving Egyptian economic and cultural independence, as well as portrayals of rural men as politically potent and culturally authentic figures seen in the works of the local avant-garde and international artists. I demonstrate that el-Deeb re-presented male peasants seen in the Agricultural Museum’s photographic displays as patriotic symbols of “great men” who contribute to Egypt’s agricultural development and create national folk arts.

Brief Bio

Lara Ayad is Assistant Professor of Art History at Skidmore College and teaches courses on African art. She received her PhD in the History of Art and Architecture and a Certificate in African Studies at Boston University in 2018. Lara credits her Egyptian-American family for her symbiotic fixations with art and science.

1) Congratulations on receiving the Saad Prize for your paper, “Homegrown Heroes: Peasant Masculinity and Nation-Building in the Paintings of Aly Kamel el-Deeb.” How did you become interested in the work of al-Deeb?

Thank you! My first encounter with Aly al-Deeb’s work was circumstantial and totally unexpected. When I landed in Cairo in September of 2014 to perform my doctoral fieldwork, I was planning to focus on the art collection of the Museum of Modern Egyptian Art there. But the MoMEA directors and staff moved most of the displayed artworks to storage by the time I arrived. Concerns about the security of the museum’s collections also made my requests to access artworks stored in the storage facilities of the museum nil. It was my search for archival documents about other museum art collections in Cairo that led me to visit the Agricultural Museum, and, by extension, to discover its phenomenal fine art collection. Aly al-Deeb’s life-size paintings of peasant men were tucked away in one of the smaller rooms of the palatial Heritage Collection building at the Agricultural Museum, and I photographed them, along with many other artworks on display.

The more I returned to my photographs of al-Deeb’s untitled series, the more intrigued I became with his subjects. There is this wonderful tension between the slightly cheesy and ethnographic feel of his realist-style techniques and his nuanced efforts to define and celebrate peasant men’s agricultural labor, artisanship, and dance practices. This makes al-Deeb one of the first formally-trained artists in Egypt to spotlight Egyptian folk arts as a key element of national cultural heritage. The result of his work at the Agricultural Museum is a powerful and complex portrait of a rising national community that was distinctly Egyptian and male. His four canvases also received many visitors during and after the museum’s inauguration in 1938 because they were originally displayed on the ground floor of one of the most popular exhibition buildings in the massive museum complex – the so-called Animal Kingdom Building.

And, yet, scholars who write about modern Egyptian art in Arabic, English, and French rarely talk about Aly al-Deeb, let alone representations of peasant men. The lack of critical writings about the Agricultural Museum and its art collection motivated me to focus on al-Deeb’s work with even more purpose. With the exception of art historians, such as Nadia Radwan, many scholars and critics have ignored the Agricultural Museum and its fascinating combination of fine art, science, and history displays. I think this is partly because it defies neat divisions that some writers have made between the fine arts and other visual modes of expression and institution-formation in twentieth-century Egypt. Aly al-Deeb’s paintings were part of a much wider exhibition space that put art in the service of science, and vice-a-versa. But they were also crucial for Egyptian government officials who wanted to make Egyptian farming, agricultural heritage, and local products sexy for an Egyptian public that they envisioned as both citizens and consumers.

Looking back, I am glad that the Museum of Modern Art did not work out for me, because it paved the way for a project focused on representations of peasant figures in an exhibition space as old, unique, and eclectic as the Agricultural Museum. And I love just about anything that people have overlooked or neglected because of that thing’s weirdness, because of its ability to challenge our expectations about what constitutes art, and about what art does to shape people’s understanding of their place in the world.

2) Your paper does an incredible job of situating al-Deeb’s work within a broader visual culture in Egypt at the time drawing on illustrations in the press, ethnographic portraits, photography, and al-Deeb’s own fine arts training to unpack the work’s iconography and cultural and political significance. At the same time, you are careful also to contextualize al-Deeb’s deployment of the peasant as a figure of the nation within an international landscape of the 1930s, relating resonances of al-Deeb’s work to the social realism of Diego Riveria and American regionalists such Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton. Can you discuss the importance of this methodology to this particular moment in the history of art in Egypt as well as to the field of modern art in the Arab world?

Al-Deeb, Rivera, and Benton alike were invested in national, as well as global, debates about rural subjects and their relationship with cultural authenticity, modernity, and even anti-colonial resistance. All of these artists framed the male farmer as the key symbolic actor in these heated debates. In this way, my essay exposes the patriarchal history of cultural populism and folk-art revival on local and international levels.

Al-Deeb’s ability to address national concerns about the role of peasant men in Egypt’s political landscape, as well as global debates about the male rural subject, has major implications for the history of art in modern Egypt. Many scholars have mapped out the relationship between Egyptian modern art, gender, and nationalism in one of two main ways: one scholarly narrative frames art production in national institutions and the avant-garde as inherently distinct and opposed; the other focuses solely on representations of women and the works of women artists. I will address the second pattern of analysis in answering the next question, but the first narrative is especially relevant here and now because there has been a flurry of exhibitions and publications about the Egyptian avant-garde of the 1930s and 40s over the past several years. Sam Bardaouil published his book about Surrealism in Egypt, and exhibitions held in Paris and Cairo have provided valuable analyses and archival information about the avant-garde Group of Art and Freedom. However, these programs and writings have sometimes drawn neat binaries between officially-sponsored and avant-garde artistic practices.

Al-Deeb’s artistic career and his paintings of peasant men reveal profound ideological synergies between the state and the avant-garde, particularly when it comes to issues of gender, cultural authenticity, and anti-colonial thought. His Agricultural Museum paintings, at first glance, seem to portray peasant men as anonymous regional types. Yet, their monumental size, abstracted backgrounds, and affinities with portraits of male politicians elevated these rural figures to the status of national heroes – ones that could save Egypt from Western cultural and economic repression through folk art practices and agricultural labor associated specifically with rural men. What’s fascinating is that al-Deeb began creating murals, paintings, and displays at national museums in Cairo shortly after creating illustrations in 1935 for the anti-establishment publications of Les Essayistes, who were headed by Georges Henein and served as a critical precursor to the more famous Art and Freedom group. Government ministers and members of the avant-garde alike were celebrating Egyptian peasant men’s artisanal skills and manual work, and they all understood these rural figures as the protagonists of Egypt’s transformation into a country that was culturally authentic, industrious, and economically independent.

Analyzing al-Deeb’s paintings of peasant men in both the Agricultural Museum context and international developments helps break down the East/West binary that, I think, persists in many written histories of modern Arab art. We are starting to move away from the traditional preoccupation we’ve had with “Are these Arab artists mimicking or resisting Western influence?” But we still have some work to do, and, because of my training in African art, I’ve found that scholars specializing in modern and contemporary African art have given all of us art historians and art critics incredibly useful frameworks for surpassing West vs. the Rest dichotomies, as well as the attendant questions of mimicry that plagued the study of African art years ago. Fleshing out the local significance of al-Deeb’s paintings in conversation with their role in Mexican and American expressions of culturally authentic manhood shows that modern Arab art often defies simple accusations of mimicry or resistance vis-à-vis “the West.”

3) Gender is an important lens in your analysis. How does your work intervene in previous studies on gender and nation-building?

I think just about every book I have read on gender and nation-building in Egypt or the Middle East focuses solely on women as subjects of analysis. The only exceptions to this are a few historical sources concerned with the formation of modern masculinities in Egypt. Wilson Chacko Jacob’s book, Working Out Egypt, and Lucie Ryzova’s examinations of the effendiyaand their cultural formation accomplish this well. There is also an important anthology on manhood in the Middle East called Imagined Masculinities, edited by Mai Ghoussoub and Emma Sinclair-Webb. Besides that, many of us scholars are guilty of swapping “women” and “gender” in our writings, and in our more casual conversations with each other about research. It makes sense that we have given more attention to women and their roles in history, politics, and art over the past few decades because general histories of the world have traditionally focused on men, and many of us are trying to challenge patriarchal writings of history. I, too, analyze representations of women in my other research projects, which stem mostly from my doctoral dissertation.

Nevertheless, I believe that making women invisible erases their contributions to our world, while making men invisible actually protects them and the pervasive nature of male dominance in most, if not all, aspects of life worldwide. I’ve stated before that the male experience, and nationalist models of masculinity, formed the backbone of populist cultural movements and regionalist practices around the globe during the period between the World Wars. And, yet, the books and articles that I pored through for information on Egyptian painting, sculpture, popular culture, and cinema rarely discussed male figures as gendered subjects. Al-Deeb created his four paintings of peasant men at a time when many countries, including Egypt, were suffering from the global economic depression, facing the dawn of yet another world war, and witnessing the deterioration of European colonial control in the so-called global South. The specter of the male body became increasingly important at this tumultuous time for symbolizing a member of a national collective that could compete on the world stage and surpass the debilitating effects of drastic economic and political change. This stood in stark contrast with artistic representations of peasant women, who often served as allegories of a country’s cultural condition or natural beauty. My hope is that my research will help people understand masculinity as something that is, and always has been, dynamic and culturally contingent, rather than “natural,” rigid, and inherently stable. A more critical lens on manhood also challenges the popular misconception that men have always navigated the world as an ungendered “standard” of human experience, against which women must always be compared.

4) One of the oft-noted commentaries in our field is the absence of centralized and/or public archives. What are the archives you mobilized in this study?

Centralized, public archives are definitely difficult to find or access in many parts of the world, but especially in Egypt right now. According to the Agricultural Museum staff, whom I talked to in 2015, the museum has no institutional papers. I am not sure how true this is, but, when digging through the museum’s own on-site library, I did have a hard time finding any books, newspaper articles, or documents with information about the founding or curation of the Agricultural Museum. The library has some excellent early twentieth-century texts on the sciences – botany, zoology – and an original copy of Description de l’Egyptethat gave some helpful clues about the motivations and education of the museum’s first directors. These men included a set of Hungarians and an Egyptian horticulturalist by the name of Muhammad Zulficar.

As I learned more about the Agricultural Museum’s affinities and shared history with other national museums of art, agriculture, science, and history, I started meeting with the directors of the Mahmoud Mokhtar Museum and the Ethnographic Museum at the National Geographic Society. The latter has a phenomenal collection of books and illustrations on the social and “hard” sciences, history, and civilization gleaned from Muhammad ‘Ali’s and the Khedive Ismail’s personal libraries.

Of course, I turned to the National Archives in Cairo, but I was only given access to the files of the Abdeen Palace, and then with additional restrictions. The MoMEA’s fabled art library, first formed by the artist Ragheb Ayad, was not an option. So, I turned to any information available at the National Archives on the School of Fine Arts, and I also looked to cultural magazine and monograph publications by and about modern Egyptian artists, located at the Dar al-Kotob section of the National Archives. Periodical features on the sciences there proved very useful, as they gave me some context for the subjects of display at the Agricultural Museum, and shed light on how important scientific study was to Egyptian nationalists at the time.

Newspapers served me well, because, as I was poring through issues of al-Ahram, al-Musawar, and other periodicals for features on the museum itself, and on agricultural-industrial expositions and fine art exhibitions, I also found fascinating advertisements. These soap and cosmetics ads portrayed all sorts of illustrated characters that helped me ground al-Deeb’s paintings in popular perceptions, as well as institutional narratives, of gender roles, racial identity, and nationhood in early twentieth-century Egypt. The Rare Books Collection at the American University in Cairo was a great source for postcard photographs of the Egyptian countryside and peasants from this period, as well as exhibition catalogues and personal literary collections of famed Egyptian cultural figures, such as the painter Salah Taher and the architect Hassan Fathy. I’ll add that the Netherlands-Flemish Cultural Institute in Cairo was a cheerful, welcoming space with well-preserved and highly accessible issues of al-Musawar– one of the only newspapers I have ever found that featured the inauguration of the Agricultural Museum in the 1930s.

I also accessed Arabic-language books with in-depth artist biographies and art criticism anthologies from people’s personal collections, particularly those of Hisham Ahmad at the Gezira Arts Center, Mostafa al-Razzaz from the Faculty of Fine Arts, Helwan, and contemporary artists Khaled Hafez, Yasser Mongy, Mohamed ‘Abla, and ‘Ezz al-Din Naguib. ‘Abla also founded a museum of Egyptian caricature in Fayoum, where you can find a small library with earlier periodicals about the folk arts, and books for purchase on the history of political cartoons and caricature in Egypt. Such sources are a fantastic avenue for examining the relationship between popular and fine arts relevant to my study of peasant men subjects. International sources came from the digitized collections found on France’s National Library website, as well as the Harvard Libraries, the latter of which often had more comprehensive and better-preserved collections of early twentieth-century Egyptian texts. All of this being said, if you want to access a centralized archive for modern Egyptian art and visual culture, you have to create it through movement in the city, travel outside of it, and, of course, through meetings with many people – both planned and impromptu.

5) What are some of the challenges and possibilities defining the study of modern art in the Arab world and Africa today?

The fields of modern African and modern Arab art today often deal with the same artists and artworks, if not the same regions of the world – many people living in Africa, and indigenous to the continent, speak Arabic as a primary language. So, historians of modern art from the African continent and other Arabic-speaking regions of the world are often dealing with the same challenges. I think the most significant challenge facing us today is dealing with the canon of art. It’s not just the canon of art made by and for western Europe and the United States that we have had to reckon with. We’re also increasingly having to confront canons of African and Arab art, respectively. Scholars, art critics, and artists from postcolonial nations in Africa and the Middle East have played a significant role in forming these latter canons. But scholars in many parts of the world want to put a spotlight on artists coming from Africa and the Arabic-speaking world because the Western canon of art has marginalized these figures. Yet, in the process of determining which artists are important to examine and learn about, you inevitably have to determine which ones are not so important. Who decides what is important? And how? Should we, as scholars and educators in higher learning institutions, base the subjects of our analyses on particular topics or issues? Time periods? Mediums? Styles?

The formation, and disintegration, of a canon of African art has come to mind, especially now, because I teach surveys of African art based on a textbook that has been out of print for years. Several of the scholars that pioneered the study of African art in its own right during the 1960s, 70s, and 80s are passing away, and there seems to be a vacuum in publications that help create guidelines for some type of canon, a guiding framework for a survey, of African art. While the traditional canon of “classical” African art focused disproportionately on sculptural works made by men without formal art training during the 19thand early 20thcenturies, primarily in rural areas of West and Central Africa, scholars of African art active over the past twenty to thirty years have been disrupting the canon. Studies of formally trained artists from Africa and the African Diaspora working in painting, multimedia installation, sculpture, and video are helping achieve this, and they are also dispelling the myth of the “ethnographic present” that sometimes created the allure of ritual, male-made artworks that drew in earlier generations of scholars. However, the downside of this development is that studies of modern African art are starting to entirely replace critical studies of the “classical” African art I mentioned before. I think we need to find some way to bridge the two camps of African art history so that we and our students can benefit from learning about African artistic production in its particular sociohistorical and cultural contexts.

The field of modern Arab art is a bit newer than that of African art, both in the U.S. and worldwide, which has an impact on determining whether there is even a canon of modern Arab art to begin with. There is certainly a canon of modern Egyptian art, particularly in the Arabic-language literature on the topic! However, I’ve noticed one or two patterns in the wider field of modern Arab art. One of the most upsetting has been the tendency of many scholars and art dealers to interchange modern Arab art with “modern Islamic art.” There is nothing inherently “Christian” about the work of, say, Andy Warhol or Pablo Picasso, so why should there be anything “Islamic” about the works of artists who identify as Arab, or who come from Arabic-speaking, or even Muslim-majority, countries? Furthermore, even when dealing with religious and spiritual themes apparent in works of art from these regions, it is important to consider that sizeable numbers of Arabic-speakers are Christians, many of whom make art themselves. I am not denying that Islam has had a major impact on many realms of life, and, in some cases, art-making. But, our fixation in the English- and French-speaking worlds on Islam as a style or defining characteristic of modern Arab art comes from our obsession with the Other in the art world, the latter of which is based on western European and American understandings of Christianity, secularism, identity, and politics. If we want to make exhibitions and publications that enrich our understanding of modern Arab art, we should think a little bigger, a little more creatively, than high-definition images of exotic Arab women with veils and “Islamic” calligraphy.

Possibilities for the studies of modern African and Arab art moving forward come to life when we put the two fields in direct conversation: how can we mobilize the methods of one field to open conceptual horizons for the other? Translated anthologies of key artist and art critical writings, such as Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, provide a great model for similar books on modern African art – many of its creators’ writings and manifestos, and the essays of African modern art critics, have yet to be published in accessible and collective form. Scholars of modern Arab art, in turn, have much to learn from those specialized in modern African art, particularly when it comes to questions of racial representation, diasporic experience, and the power of contemporary art exhibitions to represent and marginalize artist voices, and to form new art canons.

6) Can you share a little about your current research projects?Right now, I am developing my writing and research on Aly al-Deeb’s paintings of peasant men and masculinity from my dissertation and converting it into a journal article. Representations of the Sudanese and East Africans in modern Egyptian painting from the Agricultural Museum have been the main topic of a concurrent study, which I plan to develop and publish as another peer-reviewed article in the next year or so. This second project is exciting because, in it, I deal with the very question of Egypt’s racial and cultural identity vis-à-vis its home continent of Africa: is Egypt “African” or “Mediterranean”? How did Egypt’s colonial history in the Sudan impact artistic representations of the Sudanese? And what does that have to do with Africa? What I’ve found is that artworks created for the Agricultural Museum’s original Sudan section played a major role in distancing Egyptians and their modernity from the supposedly primitive condition of the Sudan, the latter of which, to many Egyptians, represented an African frontier. Gender roles played just as prominent of a role in paintings and sculptures of Sudanese and East African subjects as they did for their Egyptian counterparts found in other parts of the museum. My upcoming publications take an intersectional approach to examining the place of Sudanese male and female subjects in Egyptian nationalist models of manhood and femininity, respectively. In fact, paintings of Sudanese warriors were the antithesis to the ideal masculinity and citizenship we see represented in al-Deeb’s visual ode to heroic Egyptian peasant men. Stay tuned!