Gerschultz, Jessica. Decorative Arts of the Tunisian École: Fabrications of Modernism, Gender, and Power. Refiguring Modernism Series. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019. Illustrations. xxii + 256 pp. $106.95 (cloth), ISBN 9780271083186.

Reviewed by Anne Marie E. Butler (Kalamazoo College)

Published on H-AMCA (August, 2023)

Commissioned by Nisa Ari (Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts (CASVA), National Gallery of Art)

In Decorative Arts of the Tunisian École: Fabrications of Modernism, Gender, and Power, Jessica Gerschultz presents a momentous shift in artistic values and collaborations in twentieth-century Tunisia. Important to the context of this shift is a history of French colonization and Tunisian independence. French occupation began in the late nineteenth century and lasted until 1956, when the Tunisian Néo-Destour (New Constitution) party, led by Habib Bourguiba, succeeded in establishing a constitutional monarchy and, later, a representative democracy. During the independence movement era from the 1930s to 1956, there was a strong distinction between decorative “indigenous” arts and art typically attributed to European methods, such as painting. However, by the postindependence era of the late 1950s and 1960s, a group of modern artists that Gerschultz terms the Tunisian École (Tunisian School) were endeavoring to shift Tunisian arts away from the artisan-based, colonial modes of the past. Instead, they sought to articulate an idea of Tunisian modern art that departed from French colonial influence by drawing on traditional Tunisian forms yet infusing them with modern design. By cataloguing the development and influence of the Tunisian École, particularly within three institutional spaces for arts advancement—the École des Beaux-Arts, the École de Tunis, and the ateliers of the Office National de L’Artisanat—Gerschultz demonstrates how decorative arts in modern Tunisia, and the organizational bodies and associated figures that promoted them, were instrumental in the state’s modernization. This book therefore contributes an urgently needed account of the enmeshment of colonial investments, transnational artistic influence, artisans, state power, and gender dynamics in twentieth-century Tunisia to larger histories of global modern art.

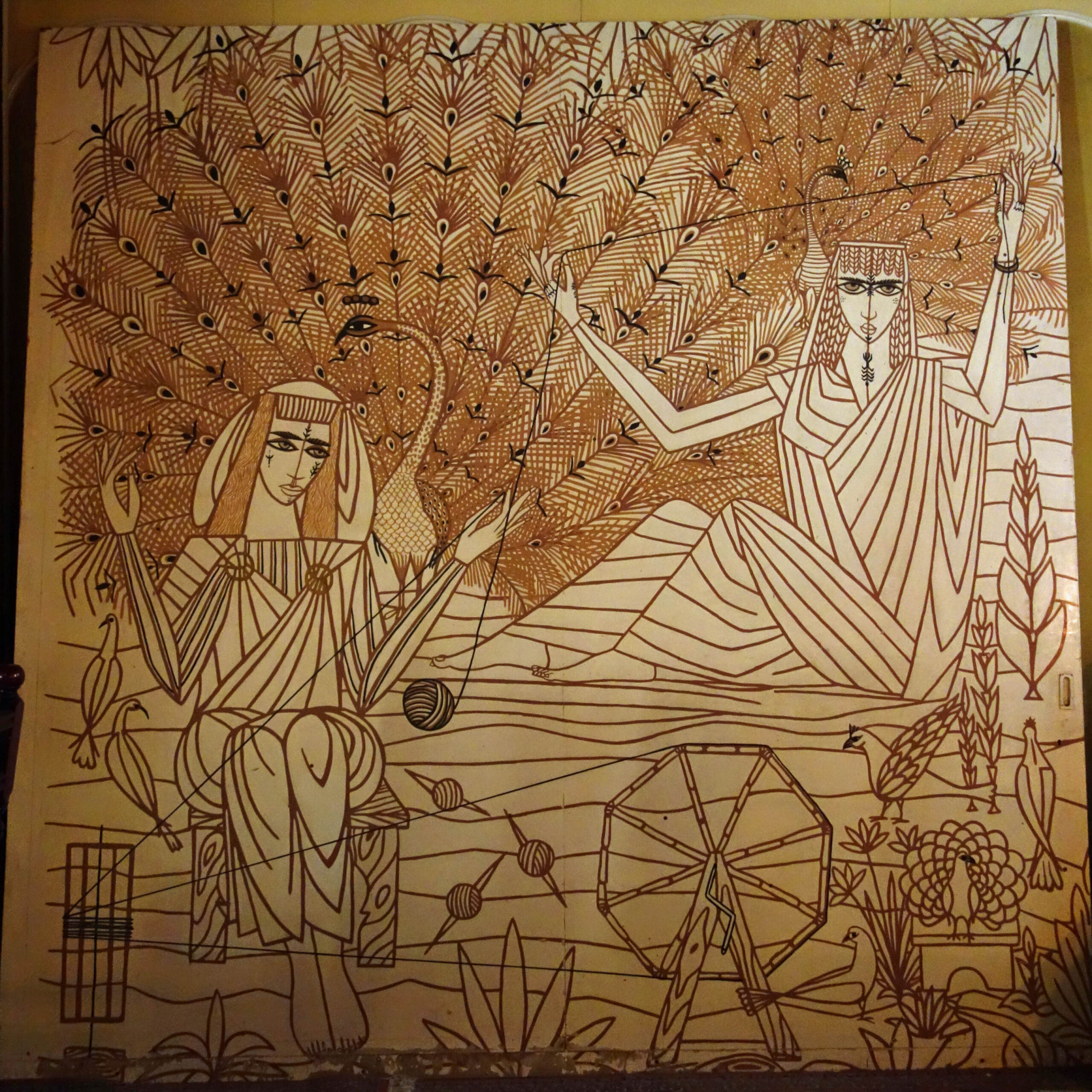

Figure 1. Jellal Ben Abdallah, Painted dining room door, Hôtel Jugurtha, Gafsa, ca. 1963. Photograph courtesy of Jessica Gerschultz, 2013.

Figure 1. Jellal Ben Abdallah, Painted dining room door, Hôtel Jugurtha, Gafsa, ca. 1963. Photograph courtesy of Jessica Gerschultz, 2013.

Figure 2. Unidentified artist, Painted scarf from the Den Den atelier, ca. early 1960s. Photograph courtesy of Jessica Gerschultz, 2013.

by H-Net Reviews

“Baya Mahieddine,” February 25-July 31, 2021, Sharjah Art Museum. . .

Reviewed by Katarzyna Faleçka (Newcastle University)

Published on H-AMCA (January, 2022)

Commissioned by Jessica Gerschultz (University of Kansas)

“Lasting Impressions” at the Sharjah Art Museum, UAE, has become an annual exhibition that celebrates the work of under-exhibited artists from West Asia and North Africa.[1] Its 11th edition formed an impressive retrospective of the work of Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine (1931-98), known for drawing on the country’s rich Amazigh, Arab, and Islamic cultural heritage. Curated by Alya Al Mulla and Suheyla Takesh, “Baya Mahieddine” (February 25-July 31, 2021) brought together seventy works by an important woman and self-taught modern artist, whose practice puts pressure on a number of art-historical terms and categorizations.

Markus Ritter, Staci G. Scheiwiller, eds. The Indigenous Lens? Early Photography in the Near and Middle East. Studies in Theory and History of Photography Series. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017. Illustrations. 372 pp. $80.99 (pdf), ISBN 978-3-11-059087-6; $80.99 (paper), ISBN 978-3-11-049135-7.

Author: Claire Gilman, curator

Reviewer: May Makki

Joanna Ahlberg, ed. Huguette Caland: Tête-à-Tête (Drawing Papers 145). New York: Drawing Center, 2021. 183 pp. $30.00 (paper), ISBN 978-0-942324-33-4.Claire Gilman, curator. Huguette Caland: Tête-à-Tête. New York: Drawing Center, June 11–September 19, 2021. .

Reviewed by May Makki (Bard College)

Published on H-AMCA (January, 2022)

Commissioned by Jessica Gerschultz (University of Kansas)

Huguette Caland: Tête-à-Tête brings together an impressive selection of over forty years of the late artist’s work. Organized in loose chronological order, the exhibition at The Drawing Center comprises a large room of early- and mid-career works, a back room of later works, and two biographical films downstairs (fig. 1; https://tinyurl.com/3suzynba). The more subtle organizational thread, however, is the use of juxtaposition and separation that deftly draws out Huguette Caland’s distinct approach to line across paintings, works on paper, caftans, mannequins, and ceramics.

Markus Ritter, Staci G. Scheiwiller, eds. The Indigenous Lens? Early Photography in the Near and Middle East. Studies in Theory and History of Photography Series. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017. Illustrations. 372 pp. $80.99 (pdf), ISBN 978-3-11-059087-6; $80.99 (paper), ISBN 978-3-11-049135-7.

Author: Markus Ritter, Staci G. Scheiwiller, eds.

Reviewer: Mira Xenia Schwerda

Reviewed by Mira Xenia Schwerda (Harvard University)

Published on H-AMCA (February, 2021)

Commissioned by Alessandra Amin (UCLA)

“No artist’s brush such an image could create” has been inscribed on a photograph of a group of poets in Shiraz taken by the photographer Mirza Hasan (1853-1915) in 1894. Iranian poet ‘Abd al-Asi ‘Ali Naqi al-Shirazi composed the poem specifically for the photograph. After declaring “Praise be to the lord for this blessed page,” he refers to the unique nature of photographs as inimitable by the painter’s brush and then begins to praise those depicted (quoted in Carmen Pérez González’s essay in the volume under review, pp. 199-200). Fourteen years earlier, the Ottoman photographer Muhammad Sadiq Bey (1832-1902) also reflected on the medium after he had taken the portrait of Shaykh ‘Umar al-Shaibi, the guardian of the Kaaba: “By means of photography, I depicted the highly esteemed one and sent him [this photograph] with the following verses: ‘My heart captured your presence in the grace and luster of the Kaaba. My heart is burning [with pain] because of the separation, and yet photographers are not condemned to burn in fire [in hell]. You, I have drawn on paper in friendship and memory” (brackets in the original; quoted in Claude W. Sui’s essay in the volume under review, p. 119).

Michael Ernst on Lynn Gumpert & Suheyla Takesh. Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s-1980s. New York: Grey Art Gallery, January 14–April 4, 2020. Exhibition and Catalogue.

Since the waning multiculturalism of liberal establishments past was eclipsed by the “nativism” of a resurgent radical right in the United States, the task of resisting the siren call of insular xenophobia has fallen in part to curators who—luckily for those of us who affirm the value of cultural exchange over border walls and militarized police—have lately dedicated ample exhibition space to non-Western modernisms. Modern and contemporary art from the Arab world has only recently slipped past the gatekeepers of canonical art history and begun decking the hallowed halls of art institutions around the globe.[1] The Barjeel Art Foundation, which has long sought to foster this development, is becoming a household name across the Northeast.[2] By organizing exhibitions, lending works, and participating in numerous pedagogical initiatives, Barjeel has consistently demonstrated its ambition to unsettle the myopic and Eurocentric historiography of modern art.[3] The steadily growing interest of Western art institutions in coeval modernisms and Barjeel’s evident drive to acquaint Western audiences with modernism from the Arab world have culminated, most recently, in Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s-1980s at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery.

Author: Afaf Zurayk, Sarah Rogers, ed.

Reviewer: Kareem Estefan

Afaf Zurayk, Sarah Rogers, ed. Afaf Zurayk: Return Journeys. Beirut: Twig Collaborative/Saleh Barakat Gallery, 2019. 96 pp.

The Art of Receiving: Afaf Zurayk’s Return Journeys

An expansive yet intimate view of a singular artist whose career has yet to be sufficiently celebrated, the monograph Return Journeys documents four decades of paintings and poems by Afaf Zurayk, many of which were recently on view for the first major retrospective of the artist’s oeuvre in her hometown of Beirut (January 18-March 1, 2019). The exhibition at Saleh Barakat Gallery and its eponymous publication offer a welcome opportunity to appraise the work of an artist whose abstract paintings and multimedia works are remarkably subtle, as Zurayk frequently opts for a small scale, employs a minimal, earthy or black-and-white palette, and prioritizes explorations of light and line over recognizable subject matter. Zurayk’s work is unmistakably personal, probing the vulnerable depths and complexities of emotion, but it is not confessional. Rather than divulge details or depict discrete situations, she continually pivots around potent symbols and forms—keyholes, eyes, faces—to reveal a subjectivity that is porous to the world, shaped in precarious relation to others and to nature.

Peter H. Christensen. Germany and the Ottoman Railways: Art, Empire, and In- frastructure. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017. 204 pp. $65.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-300-22564-8.

Reviewed by Emily Neumeier (Temple University)

Published on H-AMCA (January, 2019)

Commissioned by Nisa Ari (Massachusetts Institute of Technology

For the past thirty years or so, there has been a proliferation of scholarship exploring how dramatic shifts in international politics and technological development—in a word, modernization—impacted the built environment of the late Ottoman Empire. Zeynep Çelik’s The Remaking of Istanbul remains an important touchstone for these discussions, and more recent volumes on Damascus and Izmir have expanded our view to the provinces, where in the nineteenth century several cities around the Mediterranean flourished as cosmopolitan hubs in their own right.[1] In a departure from these studies, Peter Christensen’s new book Germany and the Ottoman Railways: Art, Empire, and Infrastructure eschews the trend of the singular urban monograph in favor of a much wider investigation of the Ottoman railroad network.

Author Sam Bardaouil

Reviewer Riad Kherdeen

Sam Bardaouil. Surrealism in Egypt: Modernism and the Art and Liberty Group. London: I. B. Tauris, 2017. Illustrations. 320 pp. $38.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-78453-651-0.

Reviewed by Riad Kherdeen (University of California, Berkeley)

Published on H-AMCA (August, 2018)

Commissioned by Sarah Dwider (Northwestern University)

Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=51391

Few modernist cultural movements spread and were adopted as widely during the first half of the twentieth century as surrealism. Initially launched in Paris following the end of the First World War, it began as a group of a few young male authors who turned to the writings of Sigmund Freud and his conceptualization of the unconscious to challenge the prevailing European epistemological orders of rationalism and positivism that they believed hindered their creative output. It quickly grew into a small but transformative cultural phenomenon that attracted a number of writers as well as visual artists in cities all over the world. Previous accounts of surrealism have largely framed it as a French invention with an eventual global distribution through francophone publication networks and beyond. What happens when, instead of retracing the one-way, hegemonic vectors of transmission from Paris to the rest of the world, we consider the development of and contributions to surrealism that occurred in places outside of Paris, London, and New York? The innovations and advancements made by writers and artists in these lesser-studied locales pluralized surrealism and, much to the discomfort of André Breton, that most protective and obtuse leader of the Parisian brand of “original” surrealism, pushed the movement in new and exciting directions.

Elisabeth A. Fraser. Mediterranean Encounters: Artists between Europe and the Ottoman Empire, 1774-1839. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2017. Illustrations. 320 pp. $89.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-271-07320-0.

Reviewed by Erin Hyde Nolan (Maine College of Art)

Published on H-AMCA (April, 2018)

Commissioned by Nisa Ari (Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

Elisabeth A. Fraser’s new book, Mediterranean Encounters: Artists between Europe and the Ottoman Empire, 1774-1839, actively decenters Europe as the locus of modern history. It gives agency to Ottoman artists and artistic accounts, exploring the entangled histories and often contradictory narratives that link these parts of the world. By looking at a group of six illustrated travel albums produced at the end of the eighteenth century, Fraser positions migration and representation as related components in a transnational system of exchange. She illustrates continuities of historic experience across the land and sea, highlighting visual accounts shaped by particular moments of contact. With a carefully theorized methodology to investigate such meetings and their materializations on the album page, Mediterranean Encounters illuminates the intercultural nature that has long defined the Ottoman Empire. Fraser’s splendidly rich analysis embraces the instability and disorientation engendered by the experience of travel and the reciprocal (though not always equal) process of borrowing visual forms and representational strategies across shifting imperial and national borders.

Kareem Estefan, Carin Kuoni, Laura Raicovich, eds. Assuming Boycott: Resistance, Agency, and Cultural Production. New York: OR Books, 2017. 273 pp. $16.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-944869-43-4.

Reviewed by Rebecca Wolff (UCLA)

Published on H-AMCA (March, 2018)

Commissioned by Alessandra Amin (UCLA)

With calls for boycotts coming from all sides of the political spectrum, the publication of Assuming Boycott: Resistance, Agency, and Cultural Production is a particularly timely publication. Given the late capitalist state of the global economy, many individuals feel as if boycotting is the most effective way to assert political power. Indeed, as editors Carin Kuoni and Laura Raicovich herald in the opening line of their introduction, “Boycott is a tool of our time, a political and cultural strategy that has rarely been more prominent than now” (p. 7). In the art world, cultural boycotts in particular have surged within the past few years to draw attention to exhibitions’ and institutions’ ties to oppressive governments, labor practices, and corporations. The contributors to Assuming Boycott turn a critical eye on this phenomenon, exploring the reasons behind cultural boycotts, their implementation, and their possible ramifications.

Author: Marie Grace Brown

Reviewer: Taylor Moore

Marie Grace Brown. Khartoum at Night: Fashion and Body Politics in Imperial Sudan. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017. 240 pp. $24.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-5036-0264-9.

Reviewed by Taylor Moore (Rutgers University)

Published on H-AMCA (February, 2018)

Commissioned by Alessandra Amin

Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=51035

How do bodies record history and place? What kinds of stories can we tell that emphasize the performed political capital, or “strategic choreography,” of women’s bodies and the fashions that adorn them as they move through the world? Marie Grace Brown’s beautifully written monograph, Khartoum At Night: Fashion and Body Politics in Imperial Sudan, is a history of northern Sudanese women’s bodies in motion during the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium (1899-1956).

In the first English-language monograph to focus on women as actors in Sudanese history, Brown nimbly weaves the quotidian movements of Sudanese women back into a historiographical tapestry that has previously kept them “fixed at home,” unconnected to the political world around them (p. 174). To do so, she engages with interdisciplinary feminist scholarship focusing on the connections of “the intimate and the global” headed by scholars such as Antoinette Burton, Tony Ballantyne, and Ann Laura Stoler (pp. 6-7). Throughout the book, Brown treats flesh as a subject of historical inquiry—one that was sometimes messy, unruly, and occasionally bursting out of the confining seams of empire.

Prita Meier. Swahili Port Cities: The Architecture of Elsewhere. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016. 230 pp. $35.00 (paper), ISBN 978-0-253-01915-8.

Reviewed by Emily Williamson (Boston University)

Published on H-AMCA (December, 2017)

Commissioned by Jessica Gerschultz

In today’s unsettled age, when globalization has sponsored a higher degree of interaction and uprooting, and as James Clifford points out, “there seem to be no distant places left,”[1] questions concerning how “elsewheres” root “here” emerge as central and urgent to our time. How do people grapple with two seemingly paradoxical human desires—to belong both to local places, people, and ideas, and to those of faraway? And second, what might the material life embodying these values, beliefs, and attitudes reveal about how and why people negotiate multiple identities? In Swahili Port Cities: The Architecture of Elsewhere, Prita Meier carefully and courageously tackles these significant questions through the particular historical context of the Swahili coast in East Africa—a place where “Islamic,” “Arab,” “Persian,” and “African” identities have intermingled and transformed for centuries. Drawing from diverse literature in art history, architecture, anthropology, and transcultural studies, Meier tells the fascinating story of the stone cities in Mombasa, Lamu, and Zanzibar and how their materiality has continuously shaped the histories, identities, values, and experiences of the people who inhabit them.

Author: New York Museum of Modern Art

Reviewer: Kirsten Scheid

New York Museum of Modern Art. Installation Following the Executive Order of January 27, 2017. . .

Reviewed by Kirsten Scheid (American University of Beirut)

Published on H-AMCA (August, 2017)

Commissioned by Jessica Gerschultz

The MoMA Visa: Modern Art after the Trump Ban

Since February 3, 2017, to ascend from the Museum of Modern Art’s atrium to the collections, visitors pass between Gilbert Baker’s unfurled Rainbow Flag (1978) and Siah Armajani’s Elements Number 30 (1990), a kiosk constructed of a diamond-plated aluminum sheet, a slanted barn door, a metal plinth, a box window tilted to reflect green light, and a rust shelf on its side. [Figure 1; http://tinyurl.com/yc2ljzv8] Understated sans serif wall text crisply describes Elements Number 30 as a piece of “vernacular architecture” and reports the artistic intention: “to substitute synergy for gestalt.” Below it, however, a second paragraph, this time in urgent italicized typeface, signals the aberrance of its installation. Like a visa, it precisely circumscribes the terms of inclusion: “This work is by an artist from a nation whose citizens are being denied entry into the United States, according to a presidential executive order issued on January 27, 2017. This is one of several such artworks from the Museum’s permanent collection recently installed, along with others throughout the fifth-floor galleries, to affirm the ideals of welcome and freedom as vital to this Museum, as they are to the United States.”

Author: Mohammed Gharipour

Reviewer: Nancy Demerdash-Fatemi

Mohammed Gharipour, ed. Sacred Precincts: The Religious Architecture of Non-Muslim Communities across the Islamic World. Leiden: Brill, 2015. xxxviii + 542 pp. $254.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-90-04-27906-3.

Reviewed by Nancy Demerdash-Fatemi (Princeton University)

Published on H-AMCA (April, 2017)

Commissioned by Jessica Gerschultz

Pluralism, Difference, Contestation, and Tolerance: Sacred Spaces of Non-Muslim Communities in the Islamic World

When I was growing up, I toften heard my my father lament the mass exodus of ethnic and religious minorities who fled Egypt in the wake of President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s exclusionary brand of Arab nationalism. Reflecting on the religiously diverse, cross-cultural dimensions of the urban Cairo of his youth in the 1940s, he would bemoan the loss of my grandmother’s talented Armenian seamstress, Madame Marie, or the disappearance of the city’s prominent Jewish mercantile community, whose contributions to the country’s burgeoning economy were tremendous, especially through the downtown department stores of Benzion, Orico, or Gattegno (stores that my family admired and frequented) that fashioned their window displays in the refined mold of Galeries Lafayette or Printemps in Paris. Out of these intergenerational memories of a cosmopolitan and heterogeneous Cairo emerged a looming, seemingly inescapable sense of nostalgia not simply for a bygone era, but perhaps more poignantly, for a period that was more tolerant, accepting of social difference, and progressive. And yet, by contrast, there were stories of obstinance, insularity, and segregationist attitudes dividing religious communities as well. One vivid and initmate account detailed the clash and subsequent prevention of a marriage between a Coptic woman and my uncle, who lived in adjacent villas in Mohandiseen and who were in love; however, even in spite of the Qur’anic allowance for Muslim men to marry women of ahl al-Kitāb, or “People of the Book” (Jews and Christians), their would-be interfaith union was deemed improprietous and unsuitable, partially on the grounds that the clans lived in such close spatial proximity to each other. Yet my family’s experience of this culturally heterogenous and dynamic Cairo was far from exceptional, as countless stories such as these live on across the diasporas of the Middle East.

Author: Stephen Sheehi

Reviewer: Tina Barouti

Stephen Sheehi. The Arab Imago: A Social History of Portrait Photography, 1860-1910.Princeton University Press, 2016. pages cm. $45.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-691-15132-8.

Reviewed by Tina Barouti (Boston University)

Published on H-AMCA (January, 2017)

Commissioned by Jessica Gerschultz

The Arab Imago: A Social History of Portrait Photography, 1860-1910, the title of Stephen Sheehi’s crucial book, urgently shifts the center of scholarship to consider the indigenista photograph, particularly its production, discourse, performance, exchange, circulation, and display in Ottoman Egypt, Lebanon, and Palestine from 1860 to 1910, thereby reversing historical narratives of Middle Eastern photography, which have focused on the production and perspective of the colonisateurs, largely overlooking the contribution of native photographers (p. xxii). Sheehi borrows the term “indigenista” from Latin American anthropologist Deborah Poole, whose examination of photography in turn-of-the-century Peru and the country’s processes of embourgeoisement parallels that of the Ottoman world, showing that the rise in portrait photography as a social practice and a growing middle class could be found in diverse regions of the global South. The time frame of Sheehi’s text is significant in that it marks the rise of the Tanzimat, a series of reforms and processes of modernization in the Ottoman Empire, and nahdah, or renaissance, in the Arab world in 1860 and the decline of the Osmanlilik project in 1910. Composed of two parts, “Histories and Practice” and “Case Studies and Theory,” The Arab Imago contains eight chapters that are oriented around two poles: the analytical and practical history of indigenista photography in the Ottoman Arab world and an abstruse theorization of the multifold levels of photography as a “social and ideological act” (p. xxxvii).

Author: Kamran Rastegar

Reviewer: Lara Fresko

Kamran Rastegar. Surviving Images: Cinema, War, and Cultural Memory in the Middle East.Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. 248 pp. $29.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-19-939017-5; $99.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-19-939016-8.

Reviewed by Lara Fresko (Cornell University)

Published on H-AMCA (May, 2016)

Commissioned by Berin Golonu

Kamran Rastegar’s Surviving Images: Cinema, War, and Cultural Memory in the Middle East treats the cinematic medium as the contested terrain of discursive battles within what he describes as the arbitrary boundary marker, that is, the Middle East. With this self-critical stance with regard to its geographical focus, perhaps dictated by the recognized academic field of area studies, Rastegar presents an encompassing postcolonial reading of cinematic production and its role in the writing of history and cultural memory through its power of representing social violence and its traumas.

Beginning his study in the late nineteenth century and extending it into the present, Rastegar traces the history of cinematic production through colonial contexts, independence struggles, and various postcolonial moments, drawing attention to the continuities as well as ruptures among these deeply intertwined histories and their subjects. Whether discussing the empire, the independent state, or the various resistances of colonizers and decolonizers, the book is as much about the power of the cinematic medium as it is about the networks of power that it is entangled in. To make this case, Rastegar tackles canonical and relatively more marginal films of various genres with particular attention to their different spheres of production and reception, local and international.

Author: Talinn Grigor

Reviewer: Shabnam Rahimi-Golkhandan

Talinn Grigor. Contemporary Iranian Art: From the Street to the Studio. London: Reaktion Books, 2014. 296 pp. Illustrations. $39.00 (paper), ISBN 978-1-78023-270-6.

Reviewed by Shabnam Rahimi-Golkhandan

Published on H-AMCA (September, 2015)

Commissioned by Sarah-Neel Smith

Untitled [Shabnam Rahimi-Golkhandran on Contemporary Iranian Art: From the Street to the Studio]

Contemporary Iranian Art: From the Street to the Studio is a lavishly illustrated book that sets out to accomplish a formidable scholarly feat: to provide an overarching history of the contemporary art of Iran, while also complicating the constructing elements of that agenda—neither “Iran” nor “history,” “contemporary” nor “art” are to remain stable and flat constructs in architectural historian Talinn Grigor’s account. Grigor demonstrates that “art”—consciously lowercased—is heavily implicated in government policy, constructions of national identity, and architecture. At the same time, she historicizes the category “contemporary” both in order to reframe existing categories of “modern” and to complicate the spatial and temporal singularity of “Iran.” In the author’s own words: “[t]he struggle of identity in modern Iran can be interpreted as multilayered and intensely contested pictorial discourse.… In post-revolutionary Iran, all of this thinking about art has to be embedded in the minutiae of strategies of power and identity, of colonial pasts and bright futures” (p. 12).

Author: Sarah A. Rogers, Eline Van Der Vlist, eds.

Reviewer: Holiday Powers

Sarah A. Rogers, Eline Van Der Vlist, eds. Arab Art Histories: The Khalid Shoman Collection. Amman: Khalid Shoman Foundation, 2014. 464 pp. $45.50 (paper), ISBN 978-90-821484-0-4.Reviewed by Holiday Powers (Cornell University, Department of History of Art and Visual Studies)

Published on H-AMCA (August, 2015)

Commissioned by Berin Golonu

Darat al Funun, which translates into “a home for the arts” in Arabic, is a platform for visual art in the Arab world that Suha Shoman opened in 1993 in Amman, Jordan. Its multiple buildings, devoted to art studios, research spaces, and exhibition spaces, host a wide variety of arts programming. In spring 2015, for example, beyond a group show featuring artists such as Adam Henein and Etel Adnan, Hamdi Attia presented an installation documenting the results of a workshop with youth and teens, Emily Jacir selected a series of films to be shown, and cultural consultant Dr. Faisal Darraj invited a guest speaker to discuss the role of the intellectual. Darat al Funun is intrinsically intertwined with the Khalid Shoman Collection, a collection started by Khalid and Suha Shoman devoted to contemporary art in the Arab world. The collection is built along the patrons’ personal interests, and shows a particular devotion to Palestinian artists and artists that have been interested in Palestine, although it also attests to the breadth of contemporary creation across the Arab world. In 2002, Darat al Funun was incorporated into the Khalid Shoman Foundation, a nonprofit established in memory of its patron. Arab Art Histories is devoted to the Khalid Shoman Collection and uses the collection as a jumping-off point to consider possible art histories that cross national lines, while also bringing together the personal recollections of the large community of artists, arts administrators and curators, and researchers who have worked at Darat al Funun, sometimes on extended residencies, and been inspired by the site.

Author: Monique Bellan

Reviewer: Yvonne AlbersMonique Bellan. Dismember Remember: Das anatomische Theater von Lina Saneh und Rabih Mroué. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag, 2013. 240 pp. EUR 59.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-3-89500-982-2.Reviewed by Yvonne Albers (Philipps-Universität Marburg)

Published on H-AMCA (June, 2015)

Commissioned by Jessica Gerschultz

Audio: Ok… But what are you guys trying to do with theatre?

Artist: We’re doing theatre.

Audio: You mean these performances you’ve been presenting this last while, you consider them theatre?

Artist: I would prefer to delay my answer for the simple reason that I don’t want to be accused of preempting criticism and blocking it.

[…]

Audio: So, why aren’t you acting…really acting?

Artist: Honestly, I’m getting offered a lot of roles…but I’m not interested in any of them.

[…]

Audio: Ok. Ok. If there aren’t any directors to your liking… Your husband…why doesn’t he produce anything for you?

Artist: He doesn’t feel like it.

Audio: Speak into the microphone.

Artist: He doesn’t feel like it.[1]

This short extract from Biokhraphia, a theater performance mocking the genre of the artist’s interview while negotiating the state of theater in Lebanon today, allows a telling glimpse into the highly conceptual, albeit provocative, (auto)critical, and nevertheless savvy theater of Lebanese artists Lina Saneh (b. 1966) and Rabih Mroué (b. 1967).

Sascha Crasnow on Anthony Downey. Uncommon Grounds: New Media and Critical Practices in the Middle East and North Africa. IB Tauris, 2014. pp. (paperback), ISBN 978-1-78453-035-8.

Uncommon Grounds: New Media and Critical Practices in North Africa and the Middle East is the first volume of a planned series of publications on contemporary art practices from the MENA region put together by Ibraaz, a self-identified online “critical forum on visual culture in North Africa and the Middle East.”[1] The volume includes contributions previously published on Ibraaz’s online platform, as well as newly commissioned essays and reproductions of artists’ works. Uncommon Grounds addresses the role of new media and technology in contemporary art practices throughout the MENA region and brings together contributions by thirty-four scholars, curators, artists, and other cultural practitioners. As the rest of the world has turned its attention toward the Middle East in the wake of 9/11, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the Arab Spring, “artists [have been] called upon (and often [have put] themselves forward) to make sense of events as they unfold,” in the words of the volume’s editor Anthony Downey (p. 14). While acknowledging the important role that artists’ works in new media have played in understanding and bringing attention to the contemporary social and political climate of the region, the volume also importantly addresses the problematics of focusing on these types of issues in art from the Middle East and North Africa. As Downey goes on to state in his introduction, “we … need to remain alert to how the rhetoric of conflict and the spectacle of revolution is deployed as a benchmark for discussing, if not determining, the institutional and critical legitimacy of these practices” (p. 17). The volume’s contributors clearly take this concern seriously, and turn their attention to issues such as the overemphasis on social media as a democratizing tool in the Arab Spring revolutions, and the appropriation of the death of Egyptian artist Ahmed Bassiony, a victim of sniper fire in Tahrir Square, by the Venice Biennale.

Nisa Ari on Bashir Makhoul, Gordon Hon. The Origins of Palestinian Art. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013. 269 pp. $35.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-84631-953-2.

Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon’s recent publication—The Origins of Palestinian Art—contributes to the modest field of modern and contemporary Palestinian art, previously sketched out by Gannit Ankori’s book Palestinian Art ( 2006) and Kamal Boullata’s book Palestinian Art: 1850-2005 ( 2009). The authors of all three publications use the national designation of Palestinian in their book titles to encompass work made by those artists from among a fragmented diaspora, a growing refugee population, those living under military occupation in the West Bank and Gaza, and even a significant number of Israeli citizens. In so doing, the authors seek to cement the relationship between the production of art and the construction of a nationalism contingent on the existence of a Palestinian identity. As a self-proclaimed third voice in the field, Bashir Makhoul and Gordon Hon’s study promises to advance the discussion of the past decade, even if the title, perhaps, points us to more of the same.

Carel Bertram, The Personal House in the Public Sphere: A Marketplace of Images in Modern Iran, on Pamela Karimi. Domesticity and Consumer Culture in Iran: Interior Revolutions of the Modern Era. Iranian Studies Series. New York: Routledge, 2013. Illustrations. 262 pp. $145.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-415-78183-1.

Pamela Karimi describes her book accurately as “a survey of Iranian domesticity and its transformations” (p. 11). With an emphasis on interaction with the West, the book begins in the late Qajar period (1794-1925) and ends in the postrevolutionary present, even into the early twenty-first century. A major focus is the pivotal, Western-oriented interim of Pahlavi Iran (1925-79), particularly the post-World War II period as Iran negotiated oil wealth and imports from the West. The author argues that the most important import was a consumer mentality that introduced Western household items and Western housing as objects of desire, with varied success and with a variety of repercussions.

Sandra Williams on Ali Behdad, Luke Gartlan. Photography’s Orientalisms: New Essays on Colonial Representation. Getty Research Institute, 2013. pp. (paperback), ISBN 978-1-60606-151-0.

The 1978 publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism left an indelible mark on scholarship on the Middle East. In the decades since, Said’s critical analysis of the exoticization of the East and its production through European visual and textual media has informed studies of photography in the Middle East, India, and North Africa and developed into the dominant framework through which such material is studied. Scholars such as Malek Alloula and Ali Behdad have relied on the Saidian model to construct a history of photography focused on the continuation of established Orientalist visual idioms inherited from painting and the repressive function of the European lens in the East. In recent years, however, scholars such as Zeynep Çelik, Christopher Pinney, and Mary Roberts have sought to complicate this model. By looking more closely at local uses and reception of photography, their work illustrates how non-Europeans used the medium as a means of self-representation, often explicitly in order to counter European-constructed stereotypes.

Alessandra Amin on Hannah Feldman. From a Nation Torn: Decolonizing Art and Representation in France, 1945-1962. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014. xvi + 317 pp. $99.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8223-5356-0; $27.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-8223-5371-3.

Hannah Feldman’s From a Nation Torn critically addresses mainstream art-historical approaches to French modernism and the cultural context that shaped its production and reception. Specifically, Feldman contests the dominant appellation “postwar” as describing the history of France from the late 1940s into the 1960s. The visual culture of this period, argues Feldman, should instead be considered “art-during-war,” given France’s uninterrupted involvement in imperial wars in Southeast Asia and North Africa between the conclusion of WWII and Algerian independence in 1962. Focusing on the Algerian War of Independence (1954-62), Feldman analyzes the complex interactions between political philosophies, public culture, and visual production during the “decades of decolonization,” highlighting the ways in which the dissolution of France’s colonial empire impacted the development of arts and aesthetic theory within French national borders. In so doing, she seeks not only to reimagine the history of French modernism as “transnational, influenced and rooted in the experience of the colonies as well as the metropole,” but to position “art objects and the visualities they engender as primary sites of theorization and analysis, rather than as secondary or tertiary epiphenomena” in the broader context of modern French history (pp. 8,15).

James Ryan, “Moving” Images: Relocating Visual Analysis in the Modern Middle East, on Christiane Gruber, Sune Haugbolle, eds. Visual Culture in the Modern Middle East: Rhetoric of the Image. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014. Illustrations. xxvii + 343 pp. $80.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-253-00884-8; $28.00 (paper), ISBN 978-0-253-00888-6.

Christiane Gruber and Sune Haugbolle’s recent edited volume Visual Culture in the Modern Middle East pulls off an impressive trick of dual timeliness. First, the primary theme of the volume emphasizes reflections on a growing interdisciplinary subfield—sensory studies—that has enjoyed a fair amount of attention in certain disciplines like anthropology for some time, but is now making its case for greater attention in fields such as history, media studies, and art history. Second, because it treats as its subject the modern Middle East, the volume broadly contextualizes recent conflicts over image making in the region—conflicts that are seemingly, and tragically, evergreen given the globalized discussion of attacks on the French newspaper Charlie Hebdo in February 2015. What readers will certainly take away from reading this volume in and after 2015 is a wider understanding of the great variety of images that are fought over, consumed, and relayed in the Middle East, including those of the prophet Muhammad but also more current figures like martyrs of the Iran-Iraq war or clerical leaders like Muqtada al-Sadr. The volume goes a long way to accomplishing what the editors set out to do in their introduction, which is to account for the place of the visual in a culture that has historically been classified as primarily auditory while also privileging, rightly or wrongly, religious culture above all else.

Edited by Massimiliano Gioni, Gary Carrion-Murayari, and Natalie Bell

Catalogue and Exhibition review: Here and Elsewhere

New York: New Museum; 2014

(279 pp; 7.8″ x 10.5″; 128 color and 152 b&w images; ISBN 9780915557059) $55 (Softcover)

by ISMAIL FAYED

“Here and Elsewhere” is the catalogue for an exhibition of the same name that ran from July to September of 2014 at the New Museum in New York. The exhibition featured the works of 45 artists from across the Arabic-speaking world and boasted that it was “not an attempt to circumscribe the participating artists solely by geography” [p. 11]. However, the actual organization of the exhibition was entirely based on geographical regions and territories. The ground floor was inhabited by artists from the Gulf (Saudi Arabia, UAE, and the GCC Collective), the first and the second floor by the Levant and Egypt, and the third floor by North Africa. This fundamental contradiction in the purported curatorial vision permeates the exhibition and its catalogue.

The opening curatorial essay by Massimiliano Gioni and Natalie Bell takes Godard’s film Ici et Ailleurs(Here and Elsewhere) (1976) as a departure point and namesake of the exhibition. Yet, the curators themselves, while elaborating Godard’s involvement in creating a propaganda film for the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), do not question the problematic history of Fatah within the larger structure of the PLO, or how that relationship changed in the wake of the Jordanian Civil War in 1970. Godard’s association with Fatah and inability to finish the film for three years should have given the curators a hint at the difficulty of any facile generalizations or superficial understanding of the complex historical and political trajectory of the region. Their choice of the film as a reference point reflects the continued misapprehension of Arab history and its complexity. It is also symptomatic of the curators’ insistence upon finding references to Western engagement with Arab culture and history as an entry point, a way to either sanction such history or make it visible and intelligible to Western audiences. However, it comes across as a self-congratulatory gesture regarding the avant-gardism of the Left in the West, as well as its historical support of national and colonial struggles in Third World countries.

The catalogue, structured around color plates of the works included in the exhibition, is divided into four main components: curatorial essays (Gioni and Bell’s opening text, followed by essays by Media Farzin and Yasmine El Rashidi); the transcribed texts of three roundtables moderated by the editors of the New York-based magazine Bidoun; and an anthology of previously published texts, also by Bidoun. While the latter do not necessarily contextualize the works presented or the positions of the artists and their processes, the curatorial essays go to great length in highlighting the history of exhibiting Arab art since the year 2000. Farzin’s essay “On the History of Contemporary Arab Shows,” with its tongue-in-cheek approach, gives an excellent overview of major international exhibitions of Arab art over the last decade. This bibliographical essay, along with the curatorial introduction, declares that “‘Here and Elsewhere’ share a critical attitude toward images, a healthy skepticism toward simplified representations” [p. 13]. This orientation may be seen as attempt to deconstruct, unpack and even denounce the pervasiveness of the politics of representation that characterize the other exhibitions. Nevertheless, the essays’ failure to recognize the problematics of memory and delve into who owns history creates a sense of repetition and the mislabeling of certain terms. This failure also suggests that it is the politics of memory that needs to be unpacked and deconstructed, not the fixation on what constitutes an authentic Arab artist or Arab art. For example, although the three roundtables are organized around the themes of “The Past,” “The Present,” and “The Future,” each of them boils down to the question of who owns history in this region and how we have come to understand it, as observed in the following statement, “If you read Tolstoy, he stands somehow for Russia. This is why archeologists speak of traces. Everything that everyone does speaks to his or her time,” [Etel Adnan, Roundtable Two, “The Present,” p. 100].

The dissonance between the artists’ statements, their positions and the significance of their work is especially evident if we consider Roundtable Three, “The Future,” the GCC collective and Simone Fattal’s answers in comparison to the answers of Marwa Arsanios and Maha Amoun. Both Maamoun and Arsanios reflect on how the notion of envisioning the future relates to their work, while Fattal’s hyperbolic answers about his own inspiration from the mythological past stand in complete contrast. So does the GCC’s insistence on the “transcendent nature” of their artistic practice: The statement “our work can definitely transcend its geographic context,” [p. 150] was equally mirrored in the exhibition. Not only was the space overcrowded, but also the rationale behind placing certain artworks next to each other was difficult to decipher. For example, are Suzan Hefuna’s drawings placed next to Anna Boghiguian’s surreal drawings and Maha Mamoun’s video because they are all women or, more specifically, all Egyptian women? The dissonance between the interlocutors in the roundtables extended into the exhibition space itself, creating a visual dissonance that was reinforced by the grouping of artists by country or region rather than by process, artistic strategy, or even interest.

The driving premise behind the exhibition and the catalogue seems to be the notion that contemporary Arab artists produce work that is meaningful and universal beyond geographical specificity. But, in fact, the works were exhibited together by that very geographical specificity, notwithstanding that many works would make more sense if exhibited alongside other “Western” artworks. A stark example is Marwan’s late Expressionist paintings, conspicuous amidst a sea of artworks that all hinge on documentary practices and what might be termed “political” work. The deeply psychological portraits of Marwan raise the question of whether he was placed there only because he is a Syrian artist or whether there is any particular resonance between him and the installations of Shuruq Harb or the multimedia installation of Wafa Hourani.

The curatorial anxiety about representation and its many pitfalls, which has marred former exhibitions, is perhaps offset by the assurance given by the director’s forward, that the exhibition “presents a collection of under-recognized figures” [p. 11]. Again, this poses the problematic proposition that somehow the choices of the curators are “radical,” or at least distinct from, the usual choices of other exhibitions. Yet, in fact, many of the artists selected are quite well-recognized, and have been featured in the majority of international Arab art shows since 2002. In addition, there is seemingly serious oversight of key artists (for example, Rana El Nemr and Sherif El Azma from Egypt).

Even in Yasmine El Rashidi’s deeply impressionistic essay, the attempt to capture the experience of growing up in Egypt during the early 1990s falls into the trap of exalting one single institution, the Townhouse Gallery, as the locus of artistic, political and cultural activism, thus failing to shed a more critical light on how that same institution single-handedly monopolized the production, dissemination and definition of contemporary art in Egypt. El Rashidi’s poetic meditation does not capture the profound struggle of a diverse, independent art scene seeking to escape the overbearing control of the state. Perhaps a simplification that might resonate with the simplistic choice of Godard’s film, or the singular focus on critiquing the politics of representation vis-à-vis the politics of memory, illuminates what was actually missing from the discussion.

The catalogue provides a much needed genealogy of the recent mania on exhibiting Arab art. On the one hand, the meticulous and thorough research is presented clearly and informatively. On the other hand, the exhibition’s obsession with deriding all previous attempts to present Arab art constitutes an ironic case of self-denial. A true breakthrough in exhibiting Arab art would have entailed a deeper engagement with specific artistic strategies rather than with artworks’ geographic or historical origins.

Ismail Fayed is an Egyptian independent writer and researcher. He has been writing on contemporary artistic practices since 2007. His writings have been featured in Mada Masr, ArteEast and Ma3azef.

Esra Akcan

Architecture in Translation: Germany, Turkey, & the Modern House

Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2012

(xiii + 392 pages, bibliography, index, illustrations) $24.95 (softcover)

by ELIZABETH ANGELL

Columbia University

Architecture is a locus of conflict in Turkey today: the protests over the redevelopment of Istanbul’s Gezi Park and Taksim Square in 2013 were not just about the destruction of green space, but also about the political connotations of the neo-Ottoman barracks and mosque planned for the area, an architectural aesthetic inspiring many highly-visible projects around the city. In this context, Esra Akcan’s innovative study of architectural translations between Germany and Turkey is a timely one: although the book focuses on the early decades of the Turkish Republic, it provides critical historical background on the cultural politics of architecture and urban planning in Turkey that continue to animate contemporary debates. Architecture in Translation is both a detailed historical account of the migration of people, plans, and ideas during the interwar period, and an innovative application of theories of translation to the medium of architecture. The book extends and enriches the terrain explored by works such as Sibel Bozdoğan’s Modernism and Nation Building: Turkish Architectural Culture in the Early Republic (2001) and Carel Bertram’s Imagining the Turkish House: Collective Visions of Home (2008), and will be of interest both to scholars of modern Turkey, and to those interested in architecture, art, and urban planning. Akcan is strikingly attentive to the differences between translating words and translating buildings, and develops her use of the theoretical framework of translation in a subtle manner—as she writes, she does not “intend to use language as an analogue for architecture, but rather to use linguistic translation as a conceptual metaphor, and to think through linguistic theories in order to construct a terminology for architectural translation” (9). Akcan makes a strong case for the applicability of this extended metaphor, for example in her contrast of “appropriating” translations and “foreignizing” ones, which is anchored in both post-structuralist literary theory and interwar Turkish debates about translation of foreign texts (15). While this approach at times obscures attention to materiality—a facet of the built environment that surfaces only occasionally in Akcan’s narrative—the extraordinary importance of language to Turkish nationalist ideology in this period makes translation a particularly compelling lens for Akcan’s exploration of the varying assumptions about culture, identity, and modernity that infused architectural theory and practice during those decades.

The book opens with a discussion of the relationship between translation, location, and modernity, drawing on the work of Walter Benjamin, Jacques Derrida, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, and Lawrence Venuti, among others, to think about what translation might mean for a visual and physical medium like architecture. The first chapter, one of the strongest, delves into the role of German and Austrian architects and planners in the construction of Ankara, the new capital of the Turkish Republic founded in 1923, as a national showcase for modernity in the form of the built environment. As Akcan observes, “the Kemalist modernization process relied on the premise that modernity was smoothly translatable to Turkey, even if it had to be inserted from above,” (51) an approach that inspired an Ankara built on the garden city model, with prominent modernist public buildings. The second chapter turns to Istanbul, exploring the former imperial capital’s wooden houses as the site of a “resistant melancholy” that questioned the changes represented in Ankara. The trope of melancholy has become something of a cliché in writing on Istanbul, but Akcan manages to bring something new to this well-troddenterritory through her extended reading of Turkish architect Sedad Hakkı Eldem’s attempts to develop a “modern Turkish house style”that fusedlocal materials with the modernist architecture he encountered in Europe (119). A third chapter examines the wave of German architects and planners who sought refuge from National Socialism in Turkey after 1933, and the impact of the Weimar-era mass housing models they and their Turkish students sought to adapt for Turkey. In her discussion of mass housing, Akcan explores the limits of “subaltern participation” in urban design. The fourth chapter examines the “convictions about untranslatability” (215) that arose from more essentialist conceptions of local or national architecture, which spurred a turn to the anonymous residential architecture of Anatolia in order to develop typologies of “the Turkish house.” Here, Akcan argues, “the struggle for individual difference in generic housing in Germany resonated in Turkey as the search for cultural difference” (246). In the final chapter, Akcan seeks avenues that transcend the “paternalistic” convictions of translatability and the “chauvinistic” ones of untranslatability to imagine a cosmopolitan alternative, finding inspiration in the work of Bruno Taut, a German architect who engaged deeply with Turkish and Japanese architectural traditions. The brief epilogue traces the subsequent careers of the architects featured in Akcan’s study and the fate of some of their buildings, structures, and plans, ending with a suggestive evocation of the lives of the Turkish migrants who since came to inhabit interwar mass housing in Germany.

Akcan’s prose is lucid and engaging.The book is beautifully designed, illustrated with architectural photographs and drawings, and the author provides a clever diagram mapping the architects’ and planners’ migrations. In the margins, running notations indicate the temporal and geographical locations (for example, “Ankara 1935-38”), a helpful resource for the reader, since as Akcan notes in her epilogue, “in unfolding the plot, I preferred intertwined histories over chronological linearity and fixed geographical separations” (284). The book draws on a rich selection of sources, including archival documents, personal diaries and correspondence, architectural curricula and periodicals, and literary texts, including the novels of Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu and the poems of the modernist innovator Nazım Hikmet. Akcan enriches her analysis of visual translation with close attention to the dynamics of linguistic translation in educational and planning contexts—for example, the translation of classes taught by German professors at Istanbul University, the bureaucratic (mis)translations of a planner’s correspondence with Ankara, and most notably, in a detailed discussion of the translation of Taut’s architectural treatise into Turkish in the 1930s (263-271). An odd exception to this sensitivity is the second chapter’s conflation of the different words for used for melancholy (melankoli, hüzün) in the Turkish source material, which might have been fascinating grounds for further discussion.

Akcan’s command of both her source material and literary theory (particularly its postcolonial strains) make for strong arguments, especiallyin her reading of architectural reflections of the clash of universalist (if Eurocentric) modernity and nationalist particularity that lay at the heart of Kemalist ideology. However, her invocation of a cosmopolitan alternative is more suggestive than conclusive. She argues for a distinction between hybridity and cosmopolitanism, suggesting that “the hybrid escapes its potential risk of maintaining separatist ideologies only when it is coupled with a cosmopolitan ethics” (277)—for many hybrid artifacts, such as the Turkish house, have been subsequently “claimed to symbolize pure nationalism” (247). The reading of Taut’s work as an expression of hybridity animated by a cosmopolitan ethics is an intriguing but limited example. Nonetheless, like the rest of this compelling book, it offers a promising avenue for future explorations of the relationship between architecture, politics, and culture.

Bibliographic note: Elizabeth Angell is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Anthropology at Columbia University.

Nadje Al-Ali and Deborah Al-Najjar, eds.

We Are Iraqis: Aesthetics and Politics in a Time of War

New York: Syracuse University Press, 2012

(320 pages, illustrations, notes, bibliography) $45.00 (cloth)

by MONA DAMLUJI

Wheaton College

View as ![]()

In the face of obscene violence and political injustice, Iraqis cope in resilient ways to maintain the semblance of normalcy in their everyday lives: preparing meals, cleaning, caring for family, telling jokes and sharing stories with friends (xxvi). However, within Iraq’s ethnically, religiously, and geographically diverse communities, collective and individual traumas have also shaped extraordinary works of creative expression and political resistance. We Are Iraqis: Aesthetics and Politics in a Time of War constitutes an impressive body of this visual, oral, literary, cinematic, and curatorial work by Iraqis.

We Are Iraqis is an English-language collection of recent work by Iraqi academics, artists, and activists living inside Iraq and around the world. The editors, Nadje Al-Ali and Deborah Al-Najjar, aim to dispel the image of Iraqis as passive victims of war by presenting powerful examples from the most imaginative dimensions of human expression. There is much to be learned from the experiences of Iraqis. Al-Ali and Al-Najjar highlight the wisdom of non-violent resistance born out through the “creativity of trauma” (xxvi). Rather than providing a tidy narrative about aesthetics and politics in Iraq during recent decades of war, sanctions and occupation, Al-Ali and Al-Najjar’s introduction primes readers with complicated problems to work through as they move through the subsequent anthology of visual and written work.

This volume brings together a variety of texts and images, including poems, personal essays, conversations, critical histories, and exhibition reviews. The result is a prism of voices that illuminates the brilliant diversity of the art/activism that has emerged to cope, contend, and counter political violence and wartime injustices in Iraq. The collection is comprised of twenty-two chapters, and the editors intend their various authors to converse in both complimentary and contradictory ways. Among the many themes examined in the volume, narratives of exile and dislocation prevail as consistent threads, and contributors include Sinan Antoon, Sama Alshaibi, and Ella Habiba Shohat. Notably, this compendium signifies an emphatic shift from top-down studies of political oppression and victimization to interdisciplinary and grounded studies of Iraq’s visual and literary cultures. In this review, I have chosen to highlight several essays most relevant to studies in the visual arts.

Nada Shabout’s essay, “Bifurcations of Iraq’s Visual Culture,” maps the theoretical and practical implications of thirteen years of sanctions and the subsequent US invasion on the production of Iraqi fine arts (i.e. painting, photography, sculpture, graphic design, etc.), which constitutes “a large part of the nation’s collective memory” (8). At stake in Shabout’s study is the reclamation and contextualization of historical narratives of Iraqi art, which have been subject to grave distortions by Western authorities since 2003 and have gone so far as to dictate current market values for Arab art. Looking toward the future, Shabout concludes that although recent artists have created new visions of Iraqi identity “predicated on invasion, war and destruction,” they can compel the world to see beyond political messages in their work and recognize their contributions in terms of aesthetic value (22).

Al-Ali’s conversation with the artist and curator Maysaloun Faraj traces her ongoing efforts to feature the work of contemporary Iraqi artists in a global context through the Strokes of Genius project, which has already resulted in a gallery exhibition, book, and online resource. In a subsequent chapter, Al-Ali provides a review of the show “Sophisticated Ways: Destruction of an Ancient City,” which featured the mixed-media work of two Iraqi artists, Hana Malallah and Rashad Salim. She writes, “Looking at their works, we are confronted with the undeniable facts of destruction: burnt canvasses, rigged materials, broken glass, torn pages, and broken pieces of wood. It’s not a pretty sight. […] But with their vision and creativity they also manage to transcend, transform, and reconstruct the debris, fragments, and ashes that are both the products and manifestations of devastation into something new, something aesthetically pleasing, even something beautiful” (151-2). Al Ali’s words capture an inherent tension between the narration of violence and the production of aesthetic value that is explored throughout the volume. Within this tension the “creativity of trauma” manifests through the words and work of the Iraqi poets, painters, essayists and filmmakers featured in this volume.

Maysoon Pachachi’s essay speaks to this tension, as it narrates the ambitions, difficulties, and successes of establishing Baghdad’s first independent film school in the wake of the US invasion. Despite the kidnappings, suicide bombings, and random violence that regularly compromised the personal security and practical capacities of students and staff, the unyielding dedication of young Iraqi filmmakers resulted in students’ completion of two film courses and ten short documentaries, in which students use moving image and montage to narrate aspects of everyday life in Iraq between 2004-2007.

Irada Al-Jabbouri’s penetrating essay, “Identity of the Numbers,” is the last of the collection. Her words comprise a graceful protest and a testimony. Al-Jabbouri chronicles the enormity and humanity of the individual stories of life and death in Iraq that have been reduced to numbing displays of empty numbers. She writes,

…reports say that 11,572 Iraqis were killed in 2005, 25,774 in 2006, 22,671 in 2007. I study the numbers…I search for the faces of the killed…I try to find out the identity of no. 530, or no. 3, or no. 200, or 29, or 2773…I ask for the number of our neighbor’s young son who left the house one day and did not come back. His family only happened to find his swollen dead body, days later…piles of bodies waiting for someone to identify them. What the number can’t tell you is that Saad was 22 years old, he loved the Barcelona football team, and he used to support the Talaba Iraqi team. He used to love dibs and rashi (date syrup and tahini, usually eaten for breakfast). He used to dream that the day would come when the girl who studies at the Teachers’ Institute would return his look (251).

Al-Jabbouri writes her memories as an act of survival, one that “resists amnesia” and promises to keep these stories alive for her daughter.

The diverse collection of essays and artistic perspectives in We Are Iraqis evocatively illustrates how the personal is political in a time of war. The editors and contributors produce a compelling critique of and counter-narrative to racist generalizations of Iraqis as either passive victims or perpetrators of violence, tropes that are promulgated and normalized through Western media. Al-Ali and Al-Najjar explain how these cogent stereotypes work to rationalize ongoing suffering in Iraq in terms of a “culture of violence” theory, which collapses specific histories and subsumes individual and collective agencies (xxx). As a whole, the anthology effectively debunks this top-down approach to understanding Iraqi culture through an illumination of specific histories and artistic agency.

Since the book lacks a transparent framework that might help readers navigate its broad range of contents (e.g. thematic structure and/or introductory essays), the individual is left to determine her or his own interpretation of the connecting themes and dialogues among authors. Reading the chapters in a progressive linear order has its advantages. The editors have curated a journey that unfolds gradually, with some unexpected twists and turns, as a novel might. On the other hand, readers without the luxury of time may be frustrated by the lack of guidance and resort to the arbitrary selection of texts based on title or author alone, missing the discursive dimensions of the volume altogether. In addition to text, images of paintings and drawings by contemporary Iraqi artists appear somewhat haphazardly amidst the various chapters. Unfortunately, this visual content remains largely unengaged by adjacent texts and thus serves chiefly to decorate the chapters rather than decode potential relationships between the visual and written narratives.

We Are Iraqis succeeds in its effort to lay bare the complexities and contradictions of societies, families, and individuals confronted with political violence and injustice. Despite their potentially disjointed organization, the multiple and contested narratives put forth in We Are Iraqis create a vital new space within the prevailing discourse on Iraq, which tends to focus on the over-deterministic lenses of sectarian difference and violence. Instead, the editors re-orient the reader towards a diverse spectrum of work created by Iraqis who practice non-violent resistance through art and activism. We Are Iraqis is recommended for courses in anthropology, art history, comparative literature, creative writing, gender and women’s studies, history, Middle Eastern studies, media studies, and peace and conflict studies.

—

Mona Damluji is the Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Islamic and Asian Visual Culture at Wheaton College (Norton, MA) and a research fellow in the Arab Council for Social Sciences working group on space.

Sonja Mejcher-Atassi, American University of Beirut, Lebanon and John Pedro Schwartz, American University of Beirut, Lebanon, eds.

Archives, Museums and Collecting Practices in the Modern Arab World

by SARAH DWIDER

Swarthmore College

In Archives, Museums and Collecting Practices in the Modern Arab World, editors Sonja Mejcher-Atassi and John Pedro Schwartz bring together a diverse group of academic voices to write on the subject of collecting in the Middle East. The book begins with a quotation from Orhan Pamuk’s The Museum of Innocence, a contemporary Turkish novel centered on the life of a fictional collector which includes the line:

“What Turks should be viewing in their own museums are not bad imitations of Western art but their own lives. Instead of displaying the Occidental fantasies of our rich, our museums should show us our own lives (1).”

While the authors acknowledge the quote’s specificity to Turkish museology, it highlights a shared challenge for the non-Occidental “other:” how to collect and present one’s own culture. As anyone familiar with the study of Arab art knows, this task of determining what, exactly, “shows us our own lives” is subject to much internal debate. This passage serves to frame the central questions of this collection of essays around the concept of self-representation, as it looks to understand how collectors and institutions in the Arab world can “show their own lives” while working against prescriptive models and internalized Euro-American assumptions about the Arab world.

Important to the framing of the essays in this book is German theorist Walter Benjamin’s discussion of collecting. In particular, Benjamin’s essay “Unpacking My Library,” published in Illuminations, lends Archives, Museums and Collecting Practices a rooted methodology for approaching Arab collecting practices. Through writing about his own relationship with his collection of books, Benjamin provides evidence for how collections and archives are shaped by “circuits of creation, transmission and reception.” This leads the editors to focus on collections as processes which are afforded meaning by collectors and their contexts. As a whole, the editors look to follow a strategy of “examining the local in a historical way, and the historical in a local way… a strategy that looks at collecting practices in their cultural and historical specificity [which] paradoxically reveals the entanglement between the local and the global (25).” Each of the essays included in the collection focuses on a localized practice in order to respond to the lines of inquiry proposed by the editors and to contribute to a more general understanding of collecting in the Arab world.

The book is organized into three sections: Local Representations of Modernity; Collecting Practices, Historiographic Practices; and From Institutional to Artistic Practices of Collecting. Each section loosely focuses on a certain facet of collecting practices in the Arab world. The first section, Local Representations of Modernity, looks closely at the collection of antique objects, such as 19th century Lebanese literary works or Palestinian amulets, as a way to both create and transmit a sense of cohesive national heritage. The second section, Collecting Practices, Historiographic Practices, analyzes the connection between history and memory, and specifically, what pieces of history are allowed to become integrated into memory. These essays focus heavily on the process of creating collections and move through a close study of exchanges made in Cairo’s paper markets, the debates over material included in Lebanese history textbooks, and the preservation of a “heritage building” in post-war Beirut. Of particular interest to those approaching the book from an art historical background is the book’s third section, From Institutional to Artistic Practices of Collecting, which covers both established and developing collecting practices centered on modern and contemporary Arab art. The rest of this review focuses specifically on the essays included in this third section.

In her essay ‘The Formation of the Khalid Shoman Private Collection and the Founding of Darat al Funun,’ Sarah Rogers looks closely at the ties between the Khalid Shoman Private Collection and the history of Darat al Funun, a non-profit contemporary arts center established by Suha Shoman in Amman in 1993. While the Shoman Collection predates the establishment of Darat al Funun by a decade or so, it is currently exhibited on rotating display at Darat al Funun and has come to closely reflect the work of the institution. In her account, Rogers first describes how the Shoman Collection has come to intersect with wider shifts in the Middle East. As she states, “certainly a collection dedicated to Arab art that spans over 30 years shares much of the shifts and transformations of artistic practices in the region” (161). In turn, the Shoman Collection points to Darat al Funun’s own contribution to these shifts in artistic practices. Much of the art included in the collection was acquired from artists who participated in the work of the institution through workshops or artists’ residencies. In this sense the collection becomes an archive not just of contemporary art works, but works which reflect Funun’s involvement in fostering art practices in both Amman and the wider context of the Middle East. In discussing these dynamics Rogers calls attention to how both Darat al Fanun and the Collection are engaged as “active participants” within a developing regional art history.

Nada Shabout’s contribution ‘Collecting Modern Iraqi Art’ provides a thorough account of “art consciousness” and collecting practices in Iraq before the US invasion in 2003. She argues that, unlike in Europe and North America, where art collecting reflected the tastes and considerations of individual collectors, art collecting in Iraq was intertwined with the process of national identity building throughout the 20th century. She describes the emergence of modern Iraqi art practices and the influential artist groups which shaped their trajectories. Artists like Jewad Selim and Faiq Hassan became established cultural leaders in Iraq and participated in a process of instilling Iraqi society with an appreciation for Iraqi modern art. This sense of cultural pride in art helped to create a well-developed culture of collecting modern art for display in the home. The government’s promotion of this collecting culture was seen in the establishment of national modern art museums like the Gulbenkian Museum and the Museum for Pioneer Artists. Shabout also outlines how Iraq developed art criticism that responded directly to the place of modern art in the context of Iraq and the place of art in nation building. She concludes her essay by marking the shifts that have occurred in Iraqi collecting practices post-2003. As a whole, this specific and localized account of 20th century art practices in Iraq serves to concretely refute widely held assumptions that visual art, collecting and criticism in the Arab world were underdeveloped before today’s contemporary practices.

Emily Doherty shifts from looking at established collecting practices to focus on emerging collections in her essay ‘The Ecstasy of Property: Collecting in the United Arab Emirates.’ This chapter specifically focuses on both government-sponsored projects and private collecting practices in Dubai and Abu Dhabi in the last decade. Doherty suggests that, at its core, the recent growth of art collecting in the Emirates is part of a larger project of establishing national identity. As she quotes from Kavita Singh, Associate Professor of Arts and Aesthetics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, “What is the first thing a country does when it wants to assert its identity? Answer: it creates a museum” (183). This is especially pertinent for the Emirates as a young nation with a small Emirati population. She situates the establishment of museums like the Louvre Abu Dhabi in this wider identity-building project and argues that it is a means of shifting the globe eastward both culturally and economically. In addition, Doherty complicates the idea that collectors in the Emirates choose to collect solely as an act of visible consumption within a hyper-consumer culture. She includes firsthand accounts from private collectors in Dubai detailing their own sense of connection to the works they purchase. Doherty’s essay counters widely circulated criticisms from art critics and historians like Didier Rykner, which characterize Emirati collecting practices and projects like the Louvre and the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi as underdeveloped or unsophisticated art consumption.

The third section ends with a moving essay by Walid Sadek entitled ‘Collecting the Uncanny and the Labor of Missing.’ Prompted by two contemporary works which grapple with the unresolved fate of those who disappeared during the Lebanese Civil War, the essay reflects on the nature of the “uncanny” and the process of mourning the absent. In reflecting on the works In This House by Akram Zaatari and Wonder Beirut by K. Joreige and Hadjithomas, Sadek calls on his reader to conceive of “how to reconfigure differently a practice of collecting that does not seek to retrieve,” as the disappeared can never fully be rescued. In this volume of essays focused on the process of rooting history and creating narrative through collecting, Sadek’s work is a solemn reflection on the limitations of this process and the gaps left in between.

While this review focuses heavily on chapters dealing directly with modern and contemporary visual art, essays from the other sections provide equally relevant insight into the dynamics of collecting and archiving in the Middle East. As the editors explain, although specific in their focus, each essay also points to wider shifts in cultural practices in the Arab world. However, despite the intentional organization of the book and the thorough introductory chapter provided by Mejcher-Atassi and Schwartz, the collection does seem slightly disjointed, as the authors’ approaches to and understanding of collecting practices in the Arab world vary widely. While some essays directly note the frameworks established by the editors and return to the central questions of the book, especially Benjamin’s idea of collections as processes, others seem more peripherally related to the frameworks outlined in the introduction. However, each of the essays is strong in its own right. Archives, Museums and Collecting Practices in the Modern Arab World is a much welcome development on previous considerations of Middle Eastern collecting practices, which have been more limited in the depth of their discussion. It joins a growing body of scholarship focused on the non-Western collector and the significance of their collections, notably Mona Abaza’s Twentieth-Century Egyptian Art: The Private Collection of Sherwet Shafei (2011) and Sylvester Okwunodu Ogbechie’s Making History: African Collectors and the Canon of African Art (2011).

Sarah Dwider is a recent graduate Swarthmore College where she completed a thesis on the intersection of art and politics in 20th century Egypt.

Bashir A. Kazimee (Ed.)

Heritage and Sustainability in the Islamic Built Environment

Southampton and Boston: WIT Press, 2012

(xvii + 213 pages, index, illustrations) $192.00 (hardcover)

by PETER CHRISTENSEN

Harvard University