Interview with Connie Sjödin, winner of the 2024 Rhonda A. Saad Prize

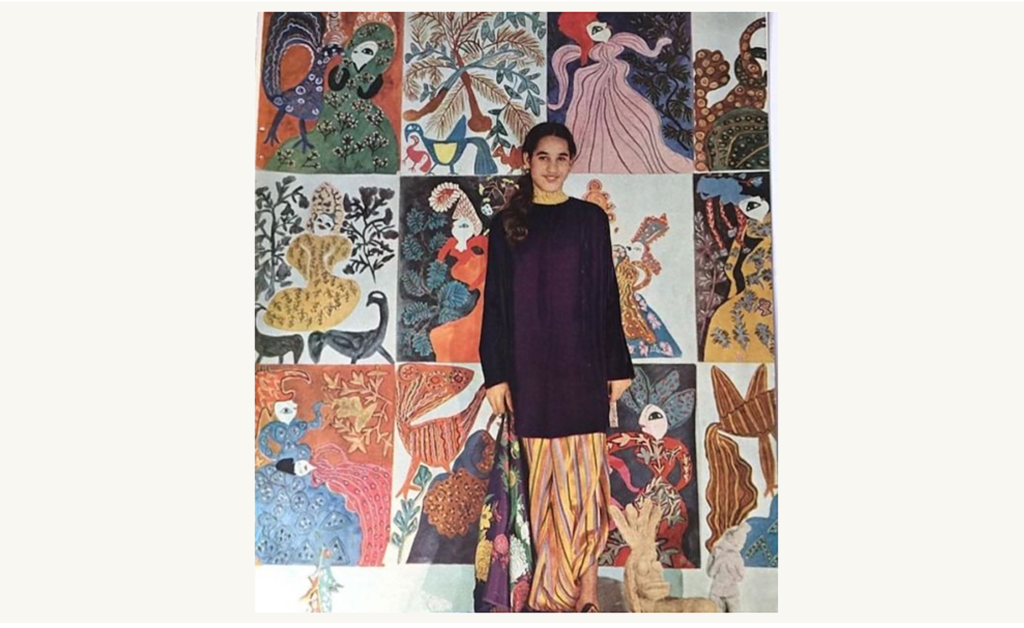

Baya Vogue France February 1948

- Can you share with us how you first became interested in the work of Algerian artist Baya Mahieddine?

I first started researching Baya Mahieddine in 2018 during my Masters in History of Art. After reading Assia Djebar’s novels as a French literature student, I was initially interested in Djebar’s art historical writings, starting with her powerful responses to the Orientalist paintings of Delacroix and Picasso. I eventually stumbled upon Djebar’s ‘Baya, le regard fleur’ in Le Nouvel Observateur. I was blown away by the intricately constructed worlds of Baya’s gouache paintings.

As part of my Masters, I submitted a short but impassioned visual analysis of a selection of Baya’s gouaches, which I felt had always been subjected to biographical and even psychoanalytical readings above all else. As I argued in this recent essay ‘Baya in Vogue’, this kind of approach risks perpetuating the original colonial reaction to her practice, which often reduced it to a natural expression of her life-story or cultural background. Of course, there are important contextual elements, as for any artist, but such a one-sided reading denies Baya any agency in the construction of her complex and incredibly consistent visual language. Initially, the colonial-biographical reading also subsumed her into a false dialectic with figures such as Matisse; she was frequently positioned as the ‘spontaneous’ counterpoint to his advanced, ‘scientific’ experiments with form. Both were experimenting with transcultural forms; both require sustained and situated formal analysis.

- Your essay begins with and centers its arguments around a photograph of the artist surrounded by her paintings, which circulated in a 1948 issue of Vogue France. What did close study of this photograph reveal to you and how did it inform your research process?

I got to see the photograph blown up to wall-size proportions at last year’s exhibition Baya, une héroïne algérienne de l’Art moderne at the Centre de la Vieille Charité in Marseille, which I visited with the curator Anissa Bouayed. Seeing it ‘life-sized’ for the first time, as if standing in the studio with Baya, it was clear that the photographer Arik Nepo (or his team), had hung her paintings behind her precisely as if they were a single tapestry, rather than as 12 individual artworks. Of course, Nepo was a fashion photographer with an eye for couture, but having read all the reductive reactions to Baya’s work from the French press in the 1940s (including Edmonde Charles-Roux’s accompanying article in Vogue), I felt that there was something more going on in his framing.

The photograph revealed to me the history of a French pseudo-ethnographic reception and commercial system that treated Baya’s work as an example of Kabylian textile culture, sometimes literally transforming it into fabrics for sale. However, it also reminded me that Baya was genuinely interested in responding to local, Indigenous material culture in her work. The problem arose as to how to write about both sides of this image: the scene of Baya in front of her gouaches, which are being treated as textiles, and the actual content of those gouaches, inspired by textiles. That’s why the essay keeps circling back to the 1948 photograph, from a critique of its colonial vision to a recognition of the role that textile actually plays in her work: I tried to weave between the two.

- While Baya’s paintings have long been absorbed into the modernist canon of “art,” your essay introduces the specter of “craft” as a vital element for understanding their distinctive dynamism—not in an Orientalist, pejorative sense, but through the lens of tissage (weaving) as put forth by Moroccan cultural theorist Abdelkébir Khatibi. How did you first become interested in exploring the intersections between Baya’s paintings and Kabylian textiles? Can you explain tissage and how you think it relates to Baya’s approach to artmaking?

In a revealing interview from 1994, Baya responds to the comparison between her own work and Matisse’s by invoking Kabylian textiles instead: ‘I was inspired by the vibrant colours worn by the women of Kabylia.’ As Rémi Labrusse has shown, Matisse’s experiments with North African textile ultimately fed his critical reflections on the limitations and realities of Western painting, as he shifted between mimetic and decorative modes (Labrusse 2021). The result is still a distinction (however productive) between his art and the craft that inspired it. Baya does something far more disruptive to the very conception of these modes; her mobilisation of textile in her paintings clearly does not adhere to the Western binary of art and craft.

But it’s hard to write against a binary or talk about ‘breaking down binaries’ if you’re still referring to its core terms. That’s why I turn to the work of Abdelkébir Khatibi. Introducing his own conceptual categories, that both recognise cultural difference but also allow space for transcultural encounter, plurality, and errantry, Khatibi writes instead about ‘image’ and ‘sign’. He ascribes ‘image’ to the Western realist tradition, and ‘sign’ to the Islamic and North African tradition; where the two meet and meld in modern art, he envisages ‘a knot of multiple artistic identities. It’s a weaving [tissage] of image and signs’ (Khatibi 2001, 9). This is what I call Khatibi’s transcultural tissage, which, with textile on my mind, helped me seriously think through the work of Baya. My core argument in the essay is therefore that each of Baya’s gouache paintings form a meticulous tissage that weaves together textile and painting, sign and image, motif and narrative. Not only that, but Baya animates each of the former through the latter, and literally brings the signs of Kabylian textile ‘to life’ through their transformation into image.

- Both your insistence on engaging with North African cultural theory and your welcoming of craft into the conversation on Baya’s work were striking. Can you speak more as to how these interventions might inform future studies of modern art from the MENA region?

Wonderful interventions have already been made using the eruptive category of ‘craft’ and even specifically textile in studies of modern art from this area, such as Jessica Gerschultz’s Decorative Arts of the Tunisian École: Fabrications of Modernism, Gender, and Power (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019). I think there’s potential for plenty more explorations which use craft to either examine the construction and retention of binaries within art history, or to break them down entirely. I would also be interested to see where other studies that respond to the work of Khatibi, who wrote extensively on popular and contemporary art from North Africa and West Asia, can take research on this region.

As for my use of North African cultural theory, it is clear from everything above that Western epistemologies are not just limited in accounting for the specificities of other cultures, but in fact inflict and perpetuate binaries (art-craft, local-universal) that enforce global hierarchies, with the ‘other’ always losing out. There are of course cultural and anticolonial theorists from the region who have been writing about epistemological violence since the 1950s. Apart from the work of Frantz Fanon, I have recently been engaging with Abdellatif Laâbi’s two powerful essays on national culturein the 1960s Moroccan journal Souffles. Alongside rightful critiques of the Western researcher ‘oriented towards the European public that he wants to win over to his Quixotic cause’, Laâbi calls for the situated production of knowledge through research into ‘our own identity’ (Laâbi 1967, 34). I cannot offer the latter, but I hope that by constantly returning to cultural theory produced in the region, such as that of Khatibi, we can begin to respond to and eventually move beyond his critique of the former.

- What were some of the challenges and rewards of this research process? Can you tell us a bit more about the archival process of this project?

One challenge, as always, comes with tantalising but unverifiable pieces of information. In an article from 1963, Jean de Maisonseul (Director of the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Algiers) mentions that Christian Dior bought 10 of Baya’s gouaches from her 1947 exhibition at Galerie Maeght, ‘thinking of drawing inspiration from them for fabrics’. It would be another fascinating example of the French fashion industry viewing Baya’s work as textile, or inspiration for it, but the Dior Archives (who were incredibly helpful) have no evidence of this purchase.

On the same trip to Marseille I also visited Baya’s papers in the Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer in Aix-en-Provence. There, I found her beautifully illustrated letters to Marguerite Caminat, photographs of herself and her husband El Hadj Mahfoud, and other archival openings, which I hope to write about more in the future. I also found a folder labelled ‘Affaire Tissu Baya’, with all the documents of a 1940s legal case involving a dressmaker with an unofficial print called ‘Baya’. For a day in the archives, opening it was like reading an Agatha Christie novel. And although it was essentially a story of copyright infringement, the ‘Affaire’ also spoke to the research I had been doing into colonial appropriations of Kabylian textiles and the Office of Indigenous Arts, established under Prosper Ricard.

Weaving these different elements together became the main challenge of the research. Also, how to balance and clearly distinguish between a critique of the Orientalist depictions of Baya, that reduced her work to textile, and my own intervention, which approaches her work through textile. Here, I felt the answer lay in the sheer overlaps between Baya’s work and Khatibi’s concept of transcultural tissage. From the archive in Aix-en-Provence to the first draft, it also took about six months of thinking and writing before I could thread the different stories and strands together.

- Can you tell us more about your current research projects?

I’m currently writing my PhD thesis ‘Aouchem 1962-1998: Algerian Signs and Third World Revolution’, which is a decolonial microhistory of the mid-century Algerian art movement Aouchem. Ten artists were associated with the group from 1967 to 1971, including Baya Mahieddine. Their name, deriving from the Arabic for tattoo (washm وشم), invokes the group’s mobilisation of Indigenous, Amazigh visual motifs across a diverse artistic output of painting, sculpture, print, and poetry. The thesis proposes a contextual history and analysis of both the discourse and visual aesthetics of Aouchem, arguing that they formed a distinct, decolonial ‘politics of form’ that connected the Amazigh sign to a Third World cultural revolution. The thesis is driven by three essential lines of inquiry: visual analysis of their artworks; oral history interviews with surviving members and their peers; and written archives including newspapers, correspondence, notes, and catalogues.

Materially, the movement only lasted four years, generating one manifesto and four group exhibitions in Algiers and the nearby town of Blida. However, this short-lived, self-proclaimed ‘avant-garde picturale algérienne’ both reflected the context of 1960s Algerian cultural decolonisation and shaped the future of Algerian artistic production. Also, members continued to apply the theoretical principles of the 1967 manifesto for the remainder of their careers. That is why I’ve decided to start the thesis in 1962 with Algerian independence and end it in 1998, the year when Baya Mahieddine dies and after the décennie noire had led to the exile of many of the group’s members.

Bibliography

Djebar, Assia. ‘Baya, le regard fleur.’ Le Nouvel Observateur, (25 January 1985): 90.

Fanon, Frantz, Richard Philcox, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Homi K. Bhabha. The Wretched of the Earth: Frantz Fanon; Translated from the French by Richard Philcox; with Commentary by Jean-Paul Sartre and Homi K. Bhabha. New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Gerschultz, Jessica. Decorative Arts of the Tunisian École: Fabrications of Modernism, Gender, and Power.Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019.

Laâbi, Abdellatif. ‘La culture nationale, donnée et exigence historique II.’ Souffles 6, (second trimestre, 1967): 29-34.

Labrusse, Rémi. ‘Deconstructing Orientalism: Islamic Lessons in European Arts at the Turn of the Twentieth Century.’ Manazir Journal 3, (2022): 145-164.