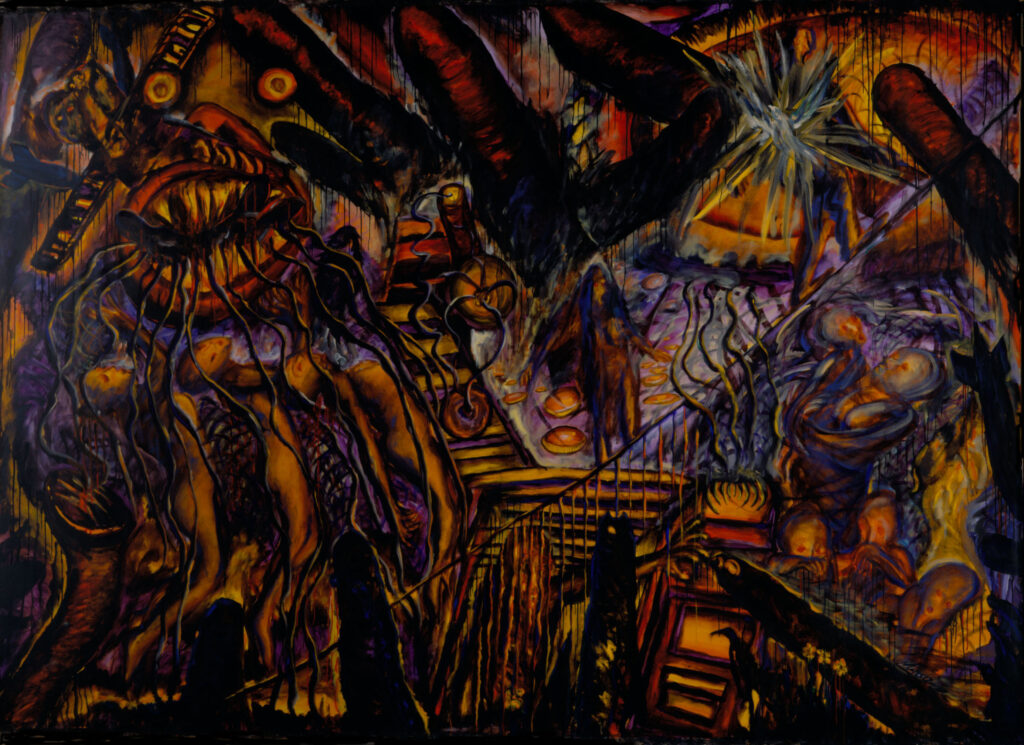

Nabil Kanso, Scorching Sparks, 1983, oil on canvas, 122 x 170 in

1. Your impetus for your curatorial project is Nabil Kanso’s mural Scorching Sparks. What led you to the artist and this particular work?

My interest in Nabil Kanso’s work developed after attending the 2022 AMCA Symposium at the University of North Texas where Kanso’s painting Gazing into the Infinite (1987) was featured in the exhibition A Banquet for Seaweed: Snapshots from the Arab 1980s at the CVAD Galleries at UNT. In particular, I was struck by the monumentality and the emotive nature of the painting. I found myself wanting to learn more about the ways the artist was grappling with seemingly deep existential questions.

I began talking with Danny Kanso and Lilly Kanso, who now care for their father’s work, in order to learn more. Together, we began imagining what a potential exhibition could look like, and how such a project could be meaningful to the numerous audiences who visit the MSU Broad Art Museum. Danny and Lilly suggested the monumental Scorching Sparks (1983) as a centerpiece for many reasons, one being that the work has never been exhibited before. As a curator, sharing something new is one of my favorite things! From there, we realized this work could be the catalyst for a meaningful conversation about the way the artist considered his home in Lebanon across his decades as a painter. For me, this brought up ideas about home and displacement that I thought audiences might find relatable, and invite engagement not only from our visitors, but also from faculty and students on campus.

2. You used the award to conduct targeted research in the Nabil Kanso estate in Atlanta, where you spent part of August 2023. Tell us a little about this experience and what you saw.

I went to Atlanta to see the archive of Nabil Kanso’s work with two goals: to see Scorching Sparks for the first time, and to gain a broader understanding of the artist’s practice. These two objectives were the foundation for building out the broader framework and checklist for the exhibition. Throughout my week-long visit, I went on a whirlwind journey through several decades of the artist’s practice ranging from tiny sketchbooks to large paintings that were so big they nearly didn’t fit in our working space.

Rachel Winter working at the Estate of Nabil Kanso, Atlanta, GA, August 2023

Rachel Winter working at the Estate of Nabil Kanso, Atlanta, GA, August 2023

On one hand, this survey allowed me to see the connections between the different bodies of work I wasn’t previously aware of, which will certainly show up in the exhibition. For example, Kanso investigated the history of Lebanon, and translated this into smaller paintings focused on more intimate moments of daily life. However, once I saw these, I realized how these prefaced his larger paintings lamenting the Lebanese Civil War. The relationship between the two portray shifting landscapes, and consider how this impacted people in Lebanon. More importantly, they also show the artist’s emotional journey, which follows through to later works where he laments crisis as people flee Iraq and Syria.

While I was aware of the way the artist thought globally, I was also surprised to learn more about Kanso’s domestic thinking during my trip. In his work, he also considered issues in the US like police brutality and racism. One could argue that this is very much an extension of the way he considered US imperialism in the region we refer to as the Middle East, but I appreciated the opportunity to see the other side of this visual thinking.

The artist was largely overlooked in his lifetime, meaning there has not been much published about his work to date. While this is a challenge to conducting research, it also presents an exciting opportunity to begin a new dialogue. I’m incredibly grateful to Danny and Lilly for not only hosting me and sharing their father’s work, but for also being incredibly generous collaborators throughout this process!

3. Were there any unexpected findings in the artist’s collection or archives?

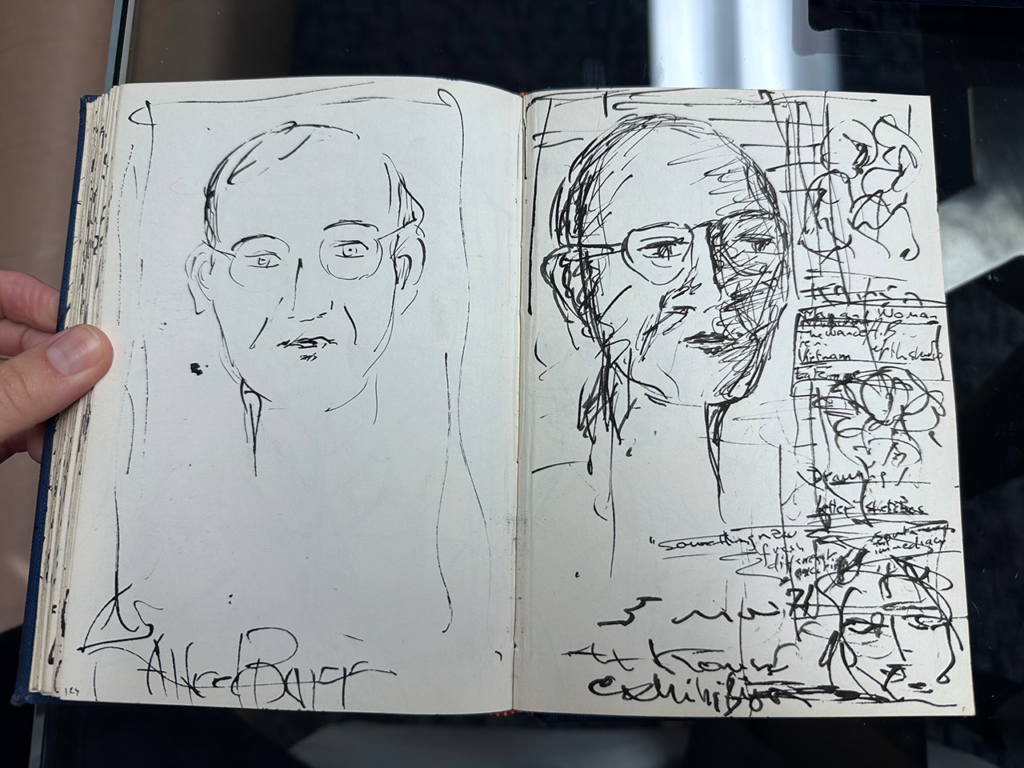

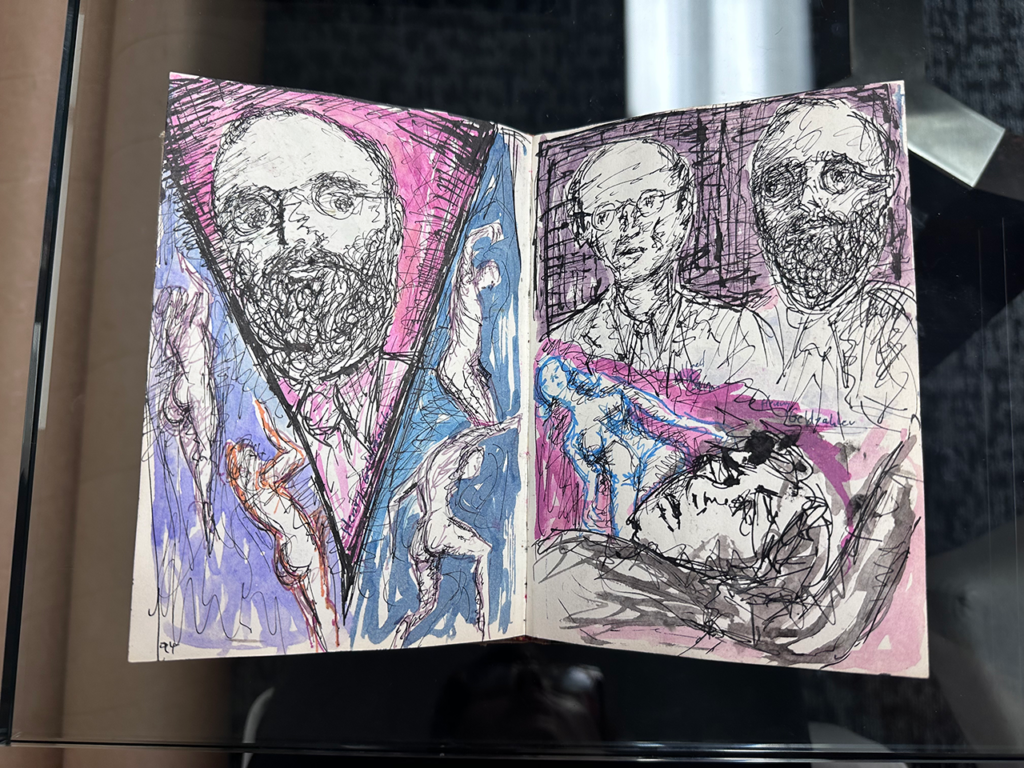

Sketchbooks by Nabil Kanso, c. 1970s. Estate of Nabil Kanso, Atlanta, GA

Sketchbooks by Nabil Kanso, c. 1970s. Estate of Nabil Kanso, Atlanta, GA

When perusing Kanso’s sketchbooks, I came across numerous gestural portraits the artist did featuring key New York art world figures, including Alfred Barr, the infamous director of MoMA, and Henry Geldzahler, a popular curator in New York. I knew Kanso lived in New York for a brief period, and it seems to me as if he was quite an extrovert then, and as such, he met numerous people. However, these sketches left me wondering about Kanso’s relationships with these people, and his larger reflections on the New York art world. An avid reader, Kanso also did portraits of various liberation figures, like those who fought in the Mexican Revolution, which were intriguing to come across as well!

4. Which artwork or type of material struck you the most?

Nabil Kanso, Untitled from the series Iraq, 2004, mixed media on board, 24 x 18 in. Estate of Nabil Kanso, Atlanta, GA

Perhaps one of the works that was most striking to me was this image from the series Iraq. Here, we see two female figures in profile, as if in motion, with what appears to be a leaning date palm under moonlight. Vertical brushstrokes break up the scene. These lines read to me as if a metaphor for or implication of the sky falling, as if the destruction and decay are bearing down on the people (and animals) who are trying to avoid such devastation. It’s a visceral image that I think about a lot, but it also brought to other mind other works by Iraqi artists like Afifa Aleiby, who was featured in the recent exhibition Theater of Operations at MoMA PS1 (2019-20).

I think about the way Kanso’s image is simultaneously general yet specific, especially in this current moment. While the artist is referencing a specific event and the circumstances leading up to it, we can imagine many different historical moments that fit into this framework.

In stylistic terms, there’s also a shift in Kanso’s artistic approach. Through simplified gestures presented on a smaller scale with more negative space, the artist still fills the work with a great deal of sorrow and tragedy that make the work no less moving, but rather reflect a new phase of his thinking about global injustices.

5. How do you plan to use this collection and archival material in your forthcoming exhibition? Where are you in this process?

Many of the wonderful findings from my research trip will be featured in a solo exhibition featuring the work of Nabil Kanso at the MSU Broad Art Museum from February–June 2025. The exhibition coincides with the 50th anniversary of the onset of the Lebanese Civil War, an event that notably impacted the artist’s life and visual thinking.

When I began this project with Danny and Lilly, my initial idea was to think about the way Kanso ruminated on the Lebanese Civil War and its many ramifications. However, as the project developed, and with the outcomes of this research trip in mind, its shape has shifted to think more broadly about home. On one hand, I remain focused on the ways Kanso thought about his former home in Lebanon, as well as the many events which changed the country. As such, the exhibition will feature some of the artist’s early work from the 1970s that study Lebanon’s history alongside larger, later works, like Scorching Sparks (1983) that speak directly to the Lebanese Civil War.

However, the new works that will be exhibited propose home as a more amorphous, malleable concept. For example, some drawings and paintings focused on Iraq and Syria show how the artist considered the way the actions of those in power in his new home (the US) impacted those abroad, suggesting both a global interconnectedness and cyclical patterns of injustice. In this way, there is also an implicit conversation about who gets to remain in their homes, and at what cost on both individual and institutional levels.

If this proposal sounds melancholic, it certainly is, and many of the works that will be in the exhibition lament the cycles of rage and sorrow that define a contemporary existential life. Yet there’s hope, in a way, for Kanso’s paintings were always meant to be a message to the world that drew attention to injustice and invited its audiences to take action—a mission that remains relevant today.

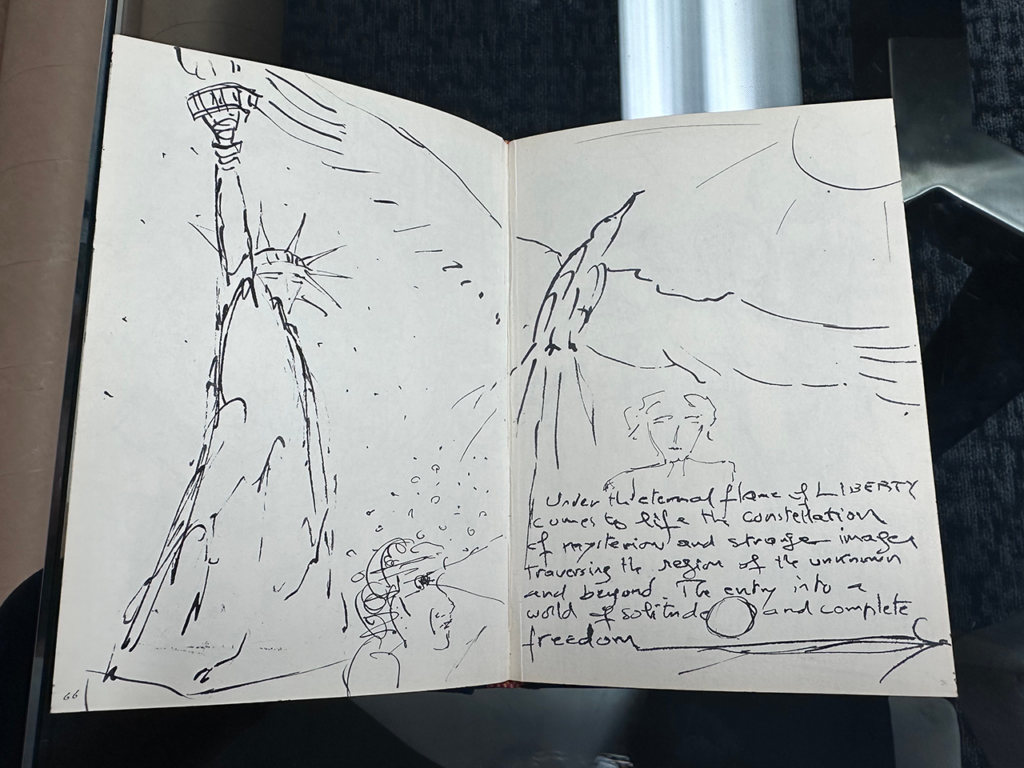

Sketchbook by Nabil Kanso, c. early 1970s. Estate of Nabil Kanso, Atlanta, GA

6. What is the desired impact of this exhibition?

When I began my role as Assistant Curator at the MSU Broad Art Museum in January 2022, I had one goal in mind: to draw attention to Arab, Iranian, and Turkish artists, specifically those in diaspora. Why? Because these threads are the ones that shape and define Michigan’s history, but which often go undiscussed for many reasons. Many people know about Dearborn and its rich history, but Greater Lansing (where I’m located) is also a part of this broader network. In my mind, inviting audiences to learn about these artists and engage with their work not only prompts them to connect with Michigan’s rich history, but also consider the many lived experiences that make up our communities.

For our local audiences (which ranges from K-12 students, community members, and university students, faculty, and staff), I hope that this exhibition is first and foremost an opportunity to learn about Nabil Kanso, who may be new to them. As an R1 research university, sharing new art historical research and presenting new artists is something I see as integral to the university’s broader research mission. However, I also want Kanso’s work to inspire people to think about home and community in the same entangled ways as he did. We each have a story about home, one which may be impacted by global events, and by sharing those stories, we can build connections and foster understanding—because nothing happens in a vacuum.

In a scholarly sense, I also want this exhibition to initiate a larger conversation in multiple art historical discourses. Kanso is one of many artists who developed his visual language and his career in the US, yet he, like many others, are left out of “American” art history, or the art history which occurred within the boundaries of the United States. I also think of people like Sari Khoury, Etel Adnan, Samia Halaby, Kamal Boullata, and so many more whose creative practices are intertwined with numerous different art historical narratives that I think we’ve yet to fully delineate. Rather than re-revising American art, I want to think more about how we can write a history of Arab diaspora and/or Arab-American art. How do we tell the stories of artists in diaspora and their artistic influences and interlocutors while defying the same art historical conventions that have previously overlooked these voices?

That we have the opportunity to even dream about what these conversations might look like is an initiative for which we must also recognize the formidable work of Salwa Mikdadi. It was her incredible effort to bring awareness to artists from the region that culminated in important projects such as Forces of Change: Artists of the Arab World at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in 1994. Her work, along with the many artists she collaborated with and who advocated for themselves when institutions refused to recognize their work, paved the way for moments such as these. Now, it’s our time to return to previously overlooked artists, and invite broader conversations about how we as scholars can continue Salwa’s legacy, document these histories, and pave the way for the next generation of scholars to further propel this movement forward.

In recognition of the pioneering work of Professor Salwa Mikdadi, AMCA is thrilled to launch The Salwa Mikdadi Research Award. Salwa’s work has been instrumental in the development of the field, culminating in the establishment of al-Mawrid Arab Center for the Study of Art at NYUAD. With the establishment of this award, we seek to highlight the importance of archival research and its dissemination while honoring the legacy of Salwa’s career.

In recognition of the pioneering work of Professor Salwa Mikdadi, AMCA is thrilled to launch The Salwa Mikdadi Research Award. Salwa’s work has been instrumental in the development of the field, culminating in the establishment of al-Mawrid Arab Center for the Study of Art at NYUAD. With the establishment of this award, we seek to highlight the importance of archival research and its dissemination while honoring the legacy of Salwa’s career.

The research travel grant ($1000) aims to help scholars realize archival research they are not otherwise able to undertake (including undergraduate students writing theses, graduate students at the early stages of planning for archival research, and lecturers and faculty lacking access to research support funds). To apply, send a brief proposal (500 words) of your intended research project and the relevance of the selected archives for the project, a short cv, and names and contact information for 2 references to info@amcainternational.org by Feb 1st. This is a biannual award cycle with first cycle applications due Feb 1st of 2023. Awardees will be announced by March 1st.

For interviews with The Salwa Mikdadi Research Award winners, please visit:

RECENT RECIPIENTS: