For daily notices about opportunities, exhibitions, and other items of interest for our field, consider subscribing to H-AMCA http://www.h-net.org/~amca/ , a moderated list-service run under the auspices of H-Net. Tiffany Floyd, currently serves as List Editor.

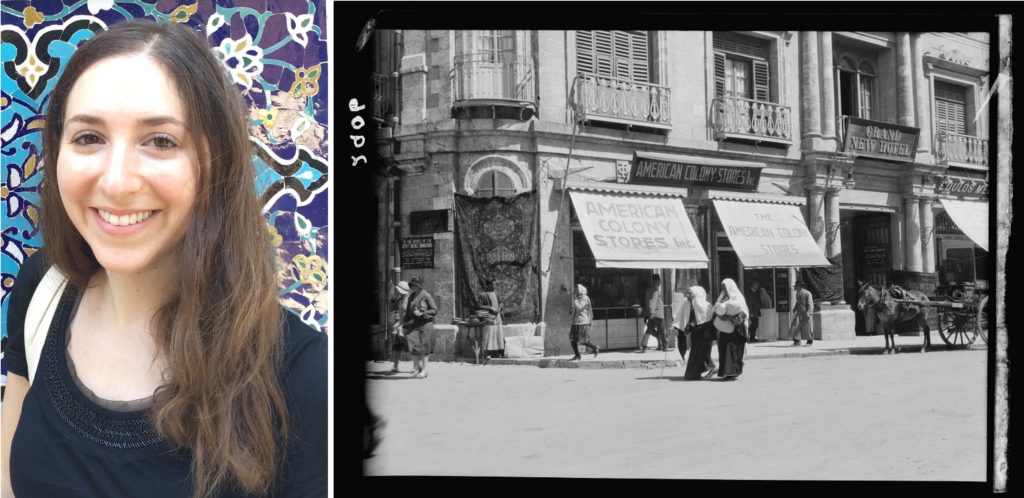

Sheyda Aisha Khaymaz

- Can you share a little about how you became interested in thinking about Hurufiyya alongside Amazighism?

My interest in Hurufiyya came about in an unconventional, backwards, as it were, manner. My doctoral dissertation centers on the use of the Tifinagh script not solely as a plastic element but also as a mode of resistance against the linguistic ideologies upheld by postcolonial nation-states across the region more accurately known as Tamazgha. I ironically used the term “backwards” because while there have been systematic studies on the use of Arabic letters in abstract painting, studies on the utilization of Tifinagh letterforms in a similar manner have been virtually absent. I, therefore, began with the lamentably under-attended Tifinagh, and from there, broadened my focus to encompass the concomitant efforts in the region. Needless to say, having Nada Shabout, who has written extensively on Hurufiyya, on my dissertation and examination committee was instrumental in guiding me to this subject.

The letter—I later expand this into the sign and the symbol in my dissertation—assumed myriad purposes for both Arab and Amazigh artists. In a sense, it became a battlefield and a signifier of cultural identity crucial in decolonization efforts. This allowed both groups to negotiate the aftereffects of colonialism and seek a distinct mode of abstraction that set them apart from their European counterparts. Although my dissertation is specifically focused on Amazigh art, juxtaposing it alongside Hurufiyya has allowed me to gain a better understanding of both, as this has revealed some shared tendencies, like liberating the letter from its semantic function, as well as points of divergence stemming from individual artists’ personal stakes and cultural loyalties.

- In your study, you highlight the importance of one’s methodological approach towards the project of decolonizing art history, and thinking about not counter-histories but rather writing histories of cohabitation and simultaneity. What do you see as some of the differences between counter-histories and histories of cohabitation? How do the stakes differ?

While both approaches aim to challenge the dominant narratives that have been shaped by colonialism and to redress its resultant effect of marginalization, counter-histories may still be viewed as being rooted in the colonial mind and perpetuating a binary worldview. My point is simply that the dichotomous nature of counter-histories reinforces a facile “us vs. them” reasoning, which precludes more tortuous instantiations of cultural and artistic production across the region in question. I still vividly recall a lecture by diasporic poet Dionne Brand titled “Writing Against Tyranny and Toward Liberation” that I watched some years ago. Ever since, I have been enthralled by the idea of writing towards liberation. But what does it really mean? Earlier in my doctoral process, I indeed endeavored to amplify counter-histories, with the aim of foregrounding all that is marginalized and sidelined. Because of the long and grueling periods of conquest, colonialism, and even nationalism that have effectively obscured much of the cultural production of colonized peoples, I foolheartedly saw this as a liberatory process. Well, I was wrong. As my research progressed, I began to realize that the very framework of liberation is highly codified, and the parameters of resistance are likewise shaped by the enduring cultural values of colonialism.

My work would have hardly progressed had I continued to write within this dualistic framework. This is where the stakes diverge. Both approaches, while well-intended, seek to address the suppression of histories by colonial hegemony. However, leveraging counter-histories can itself be viewed as a byproduct of colonialism. There is a risk here of projecting a self-congratulatory narrative of recovery and preventative safeguarding that can easily result in highly antagonistic, binary analyses, which are all too prevalent in canonical art historiography. Those we write about neither require our protection nor need to be rescued from a seeming threat of erasure. I cannot exaggerate enough the sheer number of times I emphasize this in my dissertation. One could of course be impelled to speak for the subaltern who cannot, as Gayatri Spivak figuratively put it, speak. Yet, this is the very framework that typically relegated Indigenous cultures to objects of study, rather than recognizing them as producers of knowledge to equal degree.

When we treat colonialism not as simply the expropriation of land, but as a process that entails the modification of cultural codes and priorities, as numerous postcolonial scholars have argued, we see that bifurcating the collective consciousness has been a longstanding colonial strategy of division. Examining histories simultaneously and foregrounding multiple, though not necessarily hierarchical, narratives allow us to break free from such colonial constraints. On the topic of simultaneity, I want to add that colonial time is experienced linearly with a type of codified forward movement, but the cultures of the colonized have often been construed as outside of this time. Arguing that certain events were happening concomitantly, in dialogue, exchange, and tandem with each other, poses a direct challenge to colonial logics. That is why, as I argued in my paper, the West and what Stuart Hall referred to as the Rest are not bifurcated spheres where the former commonly appropriates the latter, and the opposite is disdained. Rather, the West and the Rest have always existed in a network of relationality, for better or worse, as they had no choice but to relate to one another. These networks were always plural, and moved not in a unidirectional but in a multidirectional, multilinear, and crosswise manner.

- How do you see you your project as related to the larger field of modernism in the region?

The Western conceptualization of aesthetic modernism as an overt yet generative rupture from the so-called tradition has long since become the norm in the study of modernism. However, the notion of modernism, particularly in relation to regions outside of Europe, is itself problematic. I will spare the reader the details here, as I am confident that many are well aware that “modernism” was experienced differently across Africa and Western Asia, and was somewhat out of sync with the West. Once again, a significant portion of my dissertation attempts to unpack this vexed question of modernism, including a chapter dedicated to analyzing word definitions that are not serving our field.

Walter Mignolo, for instance, has skillfully examined the fraught relationship between modernity and tradition and arrived at the significant conclusion that both are actually colonial fabrications. The notion of “modernity” emerged at the moment of colonial encounter, and central to this process was the formulation or even invention of “tradition” and the “Orient.” Tradition, therefore, is as modern a concept as modernity, with both being manufactured by the Western imagination in opposition to one another. The writings of the Arab and Amazigh artists I have analyzed in my paper similarly imply that tradition is inherently modern, albeit requiring a reworking and a reinvigoration to capture the essence of the artists’ present moment.

The term “modernity” is also marked by a temporal dimension. In the colonial framework, as I discussed earlier, the notion of time is problematic. In my paper, when I argued that scholars must decouple Western-centric semantics from their writings, I intended to call into question the indiscriminate use of certain words, with “modernism” taking the cake. Given this, it is not my intention to situate my project within the confines of modernism. In fact, I have found it almost impossible to categorize it. My project does not seem to fit in anywhere for a good reason: it rejects the Western obsession with categorizing and refuses to be categorised. Instead, I propose a way out of the troubling and troublesome impasse of definitions by borrowing an idea from Hawad, the Kel Aïr artist, whose work I examine in my dissertation. In Houle des horizons (2011), Hawad wrote, “I am not of your clock / don’t belong / to the linear track of your time,” and concluded with the following assertion, “I am the present moment.” In my dissertation project, the term “presentness” aptly embodies an ever-flowing and evolving stream of existence that holds the full spectrum of possibility. This includes, among other things, the rights of Indigenous peoples to be simultaneously “traditional” and “modern,” if they so choose, and to refuse being confined to any preconceived categories.

- What are some of the challenges and rewards you faced researching this material?

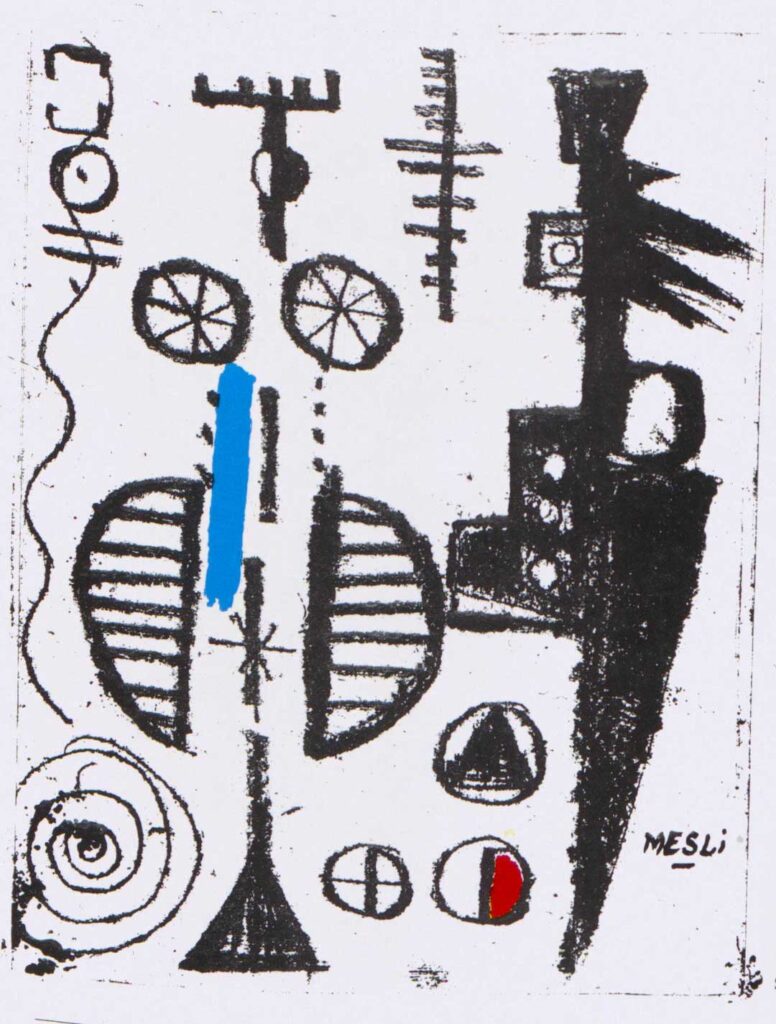

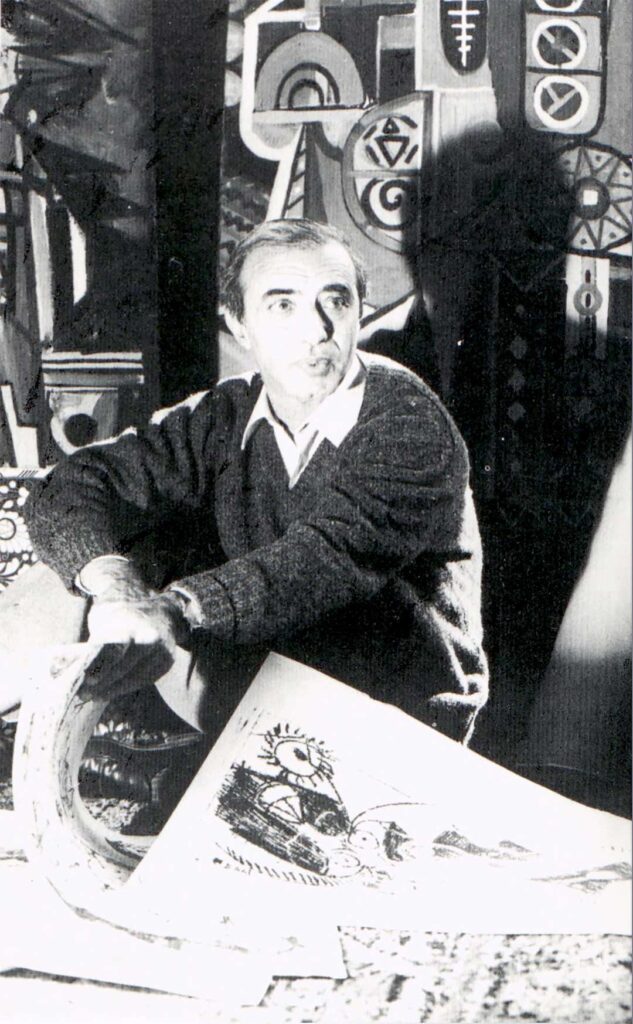

Encountering a multitude of challenges, of which I have had my fair share, is often the case when attempting to locate and access archival materials from overseas. As an example, I am currently faced with the task of locating the late artist Choukri Mesli’s works on paper. Mesli, during a research trip to the USA in 1982, meticulously produced a great number of monotypes, some of which were then acquired by undisclosed private collectors in the United States. While he did bring much of these works back to Algeria, he only shared them with a select few of his closest associates. Years later, he finally exhibited them at the M’hamed Issiakhem Gallery in Algeria. However, these works seem to be enveloped in a shroud of mystery, as no one appears to be willing to disclose their current whereabouts. To me, this is a source of frustration for a valid reason: despite identifying himself primarily as a painter, Mesli’s monotypes, a medium he regarded as transitory, offer in fact valuable insights into his sensibilities and his adeptness in handling color within an otherwise austere medium like monotype. The scholarship on Mesli’s oeuvre has always been deficient, and is almost entirely absent in the English-speaking world. His monotypes, on the other hand, appear to be even more elusive. I am actively working to address this situation and remain optimistic that I will have access to these works in the near future.

Choukri Mesli, Magical Signs, monotype, c. 1982. From the exhibition catalogue Mesli: Gouaches et Monotypes. Algiers: Galerie M’hamed Issiakhem, 1986. Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title, organized by and presented at Galerie M’hamed Issiakhem, November 20-December 15, 1986.

As someone who is naturally reserved, I am hesitant to inconvenience others. Yet, I am surprised by the number of people, both those whom I know and strangers from as far away as Algeria, whom I have approached for assistance. The challenges I mention above have also encouraged me to become more proactive and resourceful in my research, as I am learning to navigate obstacles and locate resources through various means. On a more positive note, thinking about Amazighism alongside Hurufiyya and attempting to formulate a decolonial ethical framework for this paper has proved helpful in identifying the colonial foundations of my own thinking and undoing my colonial education. I should also mention that this essay initially began as an exam response, and the process of research was primarily guided by Dr. Shabout. Passing my comprehensive exams as a result was undoubtedly one of its greatest accolades.

Choukri Mesli in the studio, discussing his monotypes, c. 1980s. © Galerie M’hamed Issiakhem & ENAD Réghaïa

- Tell us about your current research

I am currently working on a chapter focused on Hawad, an extraordinarily prolific poet and painter from the Aïr region in the Sahara, who has been living in France for quite some time. Although Hawad has been extensively researched and translated in French, and to a lesser extent in English and a few other languages, his aesthetic language, which he terms “furygraphy,” (furry + calligraphy) is directly linked to the cursive and vocalized form of the Tifinagh alphabet that the artist developed himself. “Furygraphy” is a powerful aesthetic and poetic tool that Hawad employs to resist the culture of colonialism and statism in both visual and linguistic domains. As I delve into his vast poetic oeuvre, I am grappling with his unconventional and stylistic repetitions and grounding his work within the broader socio-political history of the Sahel-Sahara region. I am eager to organize a visit with the artist this fall. As he is an outspoken political figure, I am excited to hear his insights and perspectives on the politics of his homeland.

The 2022 Rhonda A. Saad Prize for Best Paper in Modern and Contemporary Arab Art was awarded to Tina Barouti for her paper “Politicizing Art and Public Space in the Years of Lead, 1970s– 1980s.” The Rhonda A. Saad Prize review committee found that Tina’s paper offers an insightful account of art production in the 1980s, when Morocco witnessed a period of political instability and coercion of citizens under King Hassan II. Otherwise known as the Years of Lead, this period saw a series of brave ephemeral art exhibitions in Tetouan’s al-Faddan square, a prominent gathering site. Tina’s paper argues how these exhibitions played a significant role in pushing the boundaries of artmaking beyond the academy and in fostering opportunities for political activism. The committee applauds the paper for its clear prose as well as its innovative methodological approach, involving insightful observations, oral interviews, and usage of primary and secondary resources.Tina Barouti completed her PhD in the History of Art from Boston University in 2022 and is a Lecturer in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her dissertation “A Critical Moroccan Chronology: The National Institute of Fine Arts in Tetouan Since 1946,” offers the first in-depth, socio-political history of the National Institute of Fine Arts in Tetouan, illustrating how generations of artists laid the groundwork for the development of modern and contemporary art in Morocco.

The following interview, which is the sixth in our Rhonda A. Saad Prize interview series, was conducted by Pamela Karimi on behalf of AMCA in May 2022:

- How did you become interested in the subject of Tetouan’s National Institute of Fine Arts?

In 2013 I began my graduate studies and first traveled to northern Africa. By 2016 I was set to begin my preliminary dissertation research. With my short-term grant from the American Institute for Maghrib Studies, I originally wanted to conduct research in Algeria on modern painters active in the mid-twentieth century, but those plans fell through. I was able to apply my grant money to another country in the Maghrib, so I went to Morocco, where I lived the summer prior. I was very interested in examining key artists of the Casablanca Group, such as Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Chabâa, and Mohamed Melehi, but I knew that a colleague of mine had just completed her dissertation on the topic. I certainly don’t believe that only one scholar can work on the subject. In fact, the more scholarship the better, especially on underexamined non-Western art histories. However, I wanted to challenge myself and write about a topic that had not been thoroughly examined in North American scholarship. I had to quickly strategize.

I really admired the work of contemporary Moroccan artists such as Mohamed Larbi Rahhali, Younès Rahmoun, and Safaa Erruas but I did not want to concentrate solely on the twenty-first century. What these artists all have in common is that they are alumni of the National Institute of Fine Arts in Tetouan. My advisor, Dr. Cynthia Becker, encouraged me to spend more time in Tetouan and speak to as many artists as possible. In my initial investigations I learned that the art school in Tetouan was the first of its kind in Morocco and that the city (and the Rif region in which it is located) was heavily impacted by Spanish colonialism. Up until that point, my understanding of Morocco’s colonial history was entirely from a Francophone perspective. I wanted to learn more about the Spanish Protectorate and the revolutionary history of the Rif. Most importantly, I wanted to know why the Tetouan art school’s modern period was relatively underexamined.

When I returned to the United States after that preliminary research trip in 2016, I went to the Middle East Studies Association conference in Boston. I attended two events Dr. Eric Calderwood was participating in on the topic of Spanish colonialism in Morocco. He noticed me in the audience and introduced himself. Later that day he shared with me some of his writings on Mariano Bertuchi Nieto, the Spanish painter who founded Tetouan’s art school during the Protectorate period. Meeting Calderwood came at a perfect time; he became a mentor of mine and by 2021 he was on my dissertation committee. His book Colonial al-Andalus: Spain and the Making of Modern Moroccan Culture (2018) also served as a major reference for my study. After our initial meeting in 2016 I became more enthusiastic about the work and my upcoming move to Tetouan, where I lived from 2017 until 2019 with the support of a U.S. Student Fulbright Fellowship.

Installation by Bouabid Bouzaid at the fourth edition of the Spring Exhibitions, al-Faddān square, Tetouan, 1985. Bouabid Bouzaid Archive.

- Tell us a little about your approach/methodologies, and how you situate your work within the field of modern and contemporary Arab art?

I had the opportunity to present on my research approach and methodology in 2019 at a conference called “In Search of Archives: Contemporary Approaches to the Past” at silent green Kulturquartier in Berlin. Scholars Nadia Sabri and Sarah Dornhof organized the robust program. I was asked by Sabri and Dornhof to write an essay about my methodology, which will be published soon with Archive Books. In that essay I explain in detail the difficulties of conducting research on Tetouan. Essentially, I was told by the art school’s administration that an archive did not exist, so I set out to create my own. I did hundreds of studio visits, developed relationships with artists and their families, and established trust. As many scholars in AMCA have written, there is a major issue of translatability when conducting research on art history outside of the Euro-American canon. I received a U.S. State Department Critical Language Scholarship, which helped me improve my Spanish and my Colloquial Moroccan Arabic. I was then able to conduct hundreds of recorded interviews with artists in their native language. It was very important for me to do this to receive the most accurate information and show respect to the artists I was collaborating with.

The next step in my research process was to travel to artists’ homes or studios with a professional scanner and create digital copies of objects such as photographs, manifestoes, posters, exhibition flyers, newspaper articles, and other ephemera. When I started working on the Reina Sofía exhibition Moroccan Trilogy: 1950-2020 (2021) with Abdellah Karroum and Manuel Borja-Villel in 2018, I began conducting research on other Moroccan cities and focused not only on visual arts, but also literature, theatre, cinema, music, and architecture. This gave me me a much more holistic understanding of Morocco and allowed me to better contextualize Tetouan’s history. Often (with permission from artists) I would share the high-quality digital files with other scholars who were working on similar studies. On the topic of the Spring Exhibitions in Tetouan, all the information I had to work with came from these studio visits and interviews. Given the scarcity of art historical scholarship on Tetouan, I read a lot of books and articles from other disciplines, such as political science, anthropology, sociology, and comparative literature. When I arrived at the 1970s and 1980s, an especially tense time in Moroccan history, things were even more opaque. The Spring Exhibitions were an avenue to understanding that period, particularly the northern Moroccan context. In my essay “Politicizing Art and Public Space in the Years of Lead, 1970s– 1980s Morocco,” I showed that art and visual culture were far from neutral during this time.

Situating my work within the field of Arab art is something I’ve reflected on quite a bit. Throughout the first two chapters of my doctoral study, I drew many connections between modern art in Morocco and in other “Arab” countries. Morocco is a unique case study since it falls under the larger categories of Arab and African art. Despite this, it is somewhat marginalized in both subfields. Trying to neatly fit the country into a particular label is an impossible task. Cultural identity in Tetouan is even more complicated; many individuals I spoke with during my research period vocalized not identifying as Arab, Amazigh, African, or even Moroccan. There were many Muslim and Jewish families who arrived in Tetouan after their expulsion from medieval al-Andalus during the Spanish Inquisition. So today many families in Tetouan trace their origins to al-Andalus and adopt the Andalusi identity proudly. Eric Calderwood talks about this myth making and identity formation at great length in his book. This reminds me of other case studies from the so-called Arab world, especially Egyptians with Pharaonic culture or Lebanese with Phoenician identity.

In terms of the contemporary period, my work creates a historical context for Morocco’s contemporary artists. They did not emerge out of nowhere, rather they have been impacted by the groundwork laid down by generations before them.

- Can you tell us more about your dissertation/current research projects?

Since 2022 I have been lecturing in the Art History, Theory, and Criticism department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I teach a seminar on decolonization movements and their effect on arts production in Africa and West Asia. It is really rewarding to work with fine arts students and to expose them to art history that falls outside of the Euro-American canon. When I was an undergraduate art history major over ten years ago, I didn’t take any courses beyond European and American art. It is surprising that for many of my students, my seminar is their first exposure to art from Africa and West Asia.

In 2022 I was also selected as a Brooks International Fellow. With this fellowship, I participated in a six-month residency at the Delfina Foundation in London and worked in the curatorial department of Tate Modern. I was tasked with investigating networks of pan-African modernism and decolonization movements. My goal was to break down the conceptual divide that exists between Africa north and south of the Sahara. There aren’t many modern artists from northern Africa in the Tate’s collection, so I focused a lot of my attention on twentieth-century representations of Tunisians by European artists and critiqued museum didactics. I also studied the appropriation of indigenous forms by Casablanca’s artists, who are in the collection. I am currently working on publishing my research with Tate Papers.

I most recently was commissioned by a museum to write an exhibition catalogue essay about Cy Twombly’s time in Morocco and the use of photography in his artistic practice. I have always wanted to examine the influence of Morocco in his work, so I was delighted to write this. The exhibition hasn’t been announced yet so I can’t give away too much. I have also been writing a lot of arts criticism and advising galleries since returning to Los Angeles. So many people have been asking for my scholarship on Tetouan to be published – so this is my goal for the next year or two. There is a real urgency to do so since the narrative on modern Moroccan art has become so singular.

1. How did you become interested in the sculptural works of Mohammed Ghani?

Mohammed Ghani has long been one of my favorite Iraqi artists. I find his preliminary sketches to be poignantly beautiful in their stark linear simplicity and rhythm that, in fact, belies the complexities of his rendered forms. There seems to be an endless array of interpretive possibilities and each time I look at a collection of his drawings I discover new patterns, new ways that the lines move and fit together, new directions of action. Needless to say, I never grow bored of them. As a lover of visual narrative, I am also continually struck by Ghani’s versatility as a storyteller. From the sketchpad to monumental marble, his figures are dynamic, energetic, and imaginative, conveying the peaks and valleys of some of humanity’s most cherished stories and characters – from Gilgamesh to Jesus Christ to Scheherazade. Thus, exploring Ghani’s oeuvre is an exciting prospect and can be extremely satisfying in that his works always have something to give to the viewer. The longevity and variety of his career only adds to this continual well of interest. There is certainly much more to discover, and I feel privileged to be one of the scholars writing about his works.

2. Like many modern artists in the Baghdad Group of Modern Art, as well as in the region, Ghani engaged with ancient forms and archaeological artifacts like cylinder seals, orthostats, and stelae. What differentiates or stands out about Ghani’s thinking and practice from those of his colleagues?

Certainly, Ghani was a man of his time and a man of his country. That is to say, he moved within the artistic trends of mid-twentieth century Iraq wherein many artists were embracing the nation’s rich ancient heritage as a wellspring of inspiration for modern art practice. He was not alone in the pursuit of the past. However, I would argue that Ghani wasunique in that he not only embraced the iconographies, motifs, and narratives of Mesopotamian antiquity, but also the sculptural supports of his claimed predecessors. Some may say that this is simply by virtue of his medium. Yet, I think Ghani consciously sought to identify directly with Sumerian and Assyrian sculptural traditions in the modality of production, not simply representation. This is where a discussion of seals, orthostats, and stelae becomes really interesting and important. Ghani uses these forms as the foundational matrices of his practice and, I would venture further to say, he sees himself participating in the spirit of these ancient sculptural methods, finding kinship with the Mesopotamian craftsman.

3. Murals and monumental artworks were central to the career of many modern artists, with conceptual, political, and financial dimensions at times at odds with artists’ visions for themselves or for society. What tensions did you encounter during your research?

This is an important question for artists, like Ghani, who worked in Iraq during the Saddam regime. Saddam Hussein, of course, cultivated an extensive propaganda apparatus that infamously relied on historical references to bolster the personality cult of the dictator. As a monument maker, Ghani was pulled into the public art campaign of the regime and he indeed produced several works for Saddam, including public statues and commemorative medals. The implications of this are myriad, producing many questions that need unpacking. Thus, I found and continue to find it necessary to address this tension within my research and analyses of Ghani’s career in the latter half of the twentieth century. He was not the only artist to negotiate leftist ideologies and the desire for artistic freedoms with the realities of authoritarian rule that actively and violently quashed liberal thinking and free expression. Were these artists complacent in the regime’s repressive policies? Was their artistic production then somehow compromised? Did they profit from the regime’s craving for artistic support? Did artists uniformly and unequivocally adopt historical imagery only to appeal to the Ba’athist ideologies of the past? What does that mean for artists already using this imagery, like Ghani? How can we distinguish the ‘good’ art from the ‘bad’ art when all visual production is seemingly tainted with Saddam’s political agendas (even crimes)? How involved was the regime in the careers of individual artists? Was there any room for creative freedom? With these questions swirling, the tension I faced was how to maintain a critical stance whilst also giving my subject the benefit of understanding, allowing for the inevitable complications (and messiness) of historical realities.

4. One of the hallmarks of our field is the relative absence of centralized and/or public archives. What archives did you consult for this study? What challenges have you faced in accessing them?

The relative lack of official archives and easily available primary source documents is indeed a challenge, but also an opportunity. In the place of institutionally organized archival repositories there are networks of people. Establishing these networks takes time and trust, but I have found that Iraqis are extremely generous, proud of their culture, and passionate about sharing it. My work on Mohammed Ghani, for instance, was immeasurably aided by a series of individuals who shared source material and stories, primary among them was Hajer Ghani, the artist’s daughter, and her mother Ghaya al-Rahhal. I really cannot thank Hajer enough for her willingness and availability to help with all my inquiries. Also, during the initial stages of research, I was fortunate to travel to Amman where I worked with Ameena al-Shawi and Dr. Hasanain al-Ibrahimi at the wonderful Ibrahimi Collection and Library. Dia al-Azzawi’s studio library in London also proved a rich archive for this research and, of course, if you look hard enough there are always nuggets of gold in places like the British Library. In terms of personal papers – sketchbooks, letters, and the like – these remain primarily in the private archives of artists and their families. Things, however, are changing as people realize the value of what they have and seek institutional support to make documents available to a wider public.

Studying monumental, public artworks produced in and around Baghdad provides its own set of research challenges. Many of the works I discuss in my study rely heavily on the locations in which they were commissioned, created for, and placed. Yet, I was unable to travel to Baghdad to see the monuments in situ. This is where those networks of people were indispensable and, oddly enough, social media proved fruitful in obtaining current images and anecdotes about Ghani’s Baghdadi monuments.

5. How does your research build on or differ from other studies of modern and contemporary art in Iraq and/or elsewhere?

My research is indebted to the tireless work of scholars and writers like Nada Shabout, Zainab Bahrani, May Muzaffar, and more recently Saleem al-Bahloly who have paved the way for more in-depth analyses of individual Iraqi artists and their practices. The details of my study of Mohammed Ghani’s career are based in the critical writings of Jabra Ibrahim Jabra and Shawkat al-Rubaie, critics who wrote extensively on the artist’s sculptures in various publications from the 1960s into the 1990s. It is common in these writings and in the scholarship of today to find Ghani discussed in relation to his love of Iraqi history – identifying with the stories, the characters, and the connections. Yet, Ghani’s use of antiquity – its stories, iconographies, and methods – is not fully excavated for deeper art historical meanings. Indeed, his use of the past is taken for granted with the ‘whys’ and ‘hows’ left largely unexplored. In my study, I hope to bring new methodological perspectives to the investigation of Ghani’s relief practice in order to ask how exactly is antiquity being utilized in the artworks themselves, why are references to the ancient past significant within the artist’s career but also within larger paradigms of modern art practice in Iraq. By using methodologies and theories like visual narrative, mythology and time, and to some extent artist biography, I am seeking to suggest new ways to conduct rigorous visual analyses, hopefully as a means to allow Ghani’s artworks to speak beyond a referential language (the ‘what’ questions) and move into the spirit of the works.

6. Can you tell us more about your dissertation/current research projects?

My study on Mohammed Ghani is part of my larger dissertation project that uses methodologies of time to investigate the works of Ghani, Dia al-Azzawi, and Faisel Laibi Sahi. In particular, I am interested in the how these artists forged a relationship to Iraq’s ancient Mesopotamian past through various means of cultural connection and, by extension, what these connections meant in the larger contexts in which these artists practiced.

1. What led you to study the work of Rifat Chadirji?

In the summer of 2018, my PhD cohort traveled to Beirut to fulfill the summer research component of our program, an intensive two-week research trip to Lebanon. I could not travel with them. Due to the Trump administration’s travel ban, being an Iranian, I was unable to leave the US as it was more than likely that the US wouldn’t allow me to come back: the actual fate of many other Iranian PhD students who were stranded during the four years of the travel ban. Even though I could not travel to Beirut, I still had to fulfill the summer research requirement. My department was supportive, and my advisor, Hannah Feldman, suggested a brilliant alternative plan: Working on the Rifat and Kamil Chadirji archive which had been relocated from the Arab Image Foundation (AIF) in Beirut to the MIT Aga Khan Documentation Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts. My first encounter with the collection was that of intimidation and awe at the large scale of materials ranging from binders, negatives, contact sheets, prints, ephemera, to mention a few, all related to Rifat Chadirji’s practice and his professional interests. To navigate my way through the archive I started with what attracted my attention most, the binders of printed black and white photographs labeled by Rifat Chadirji with handwritten categories such as “research,” “skills,” “shopping,” “production,” “entertainment.” These binders holding the photographs of everyday activities of Iraqi people that Chadirji took in the 1960s through early 1980s were brimming with life! It seemed to me that I found among these images what was lacking in my work until then. Whereas my research hitherto was mostly focused on the macrolevel critical analysis of the dynamics of selection, circulation and representation of art works from the Middle East in the institutions outside of the region, what I encountered through Chadirji’s collection was an intact ensemble of images, each packed with a plenitude of on-the-ground everyday experiences. I distinctly remember one of the first photographs that fascinated me was from the “Shopping” series, and it depicted the interior space of a tobacco store. In the center of the frame stood a middle-aged shopkeeper. The ceiling light, the only light source of the picture, singled him out from the darker setting. The walls around him were covered with finely carved dark wood cabinets, while he calmly and confidently stared at the camera with his glowing presence in this tenebristic photograph. The unguarded, friendly and proud pose of the man directly looking at the camera was captivating. When looking at these images, the most urgent question for me was to find out Chadirji’s underlying logic of grouping the photographs, the archive’s system of visibility so to speak. Working on Chadiriji’s photographs was really fulfilling as it brought together two main aspects of my research interest: photography and theories of space.

Even though the travel ban aimed to impede the mobility and scholarly growth of people like me, I am so grateful to my advisor, Chadirji’s exceptional archive, and AMCA’s recognition of this paper, which turned this obstacle into a platform for me to further expand my knowledge and more firmly situate my work within the field. In addition, the fact that Rhonda A. Saad, like me, pursued her PhD in the art history department at Northwestern and was also Hannah’s advisee, makes this award even more meaningful to me.

2. Chadirji’s collection of about 90,000 images of people and public spaces in Iraq remains intact and has been housed in several locations. This is quite rare in our field, where archival records are often scattered and incomplete. Can you tell us more about the history of this archive? What are some of the rewards and challenges of working through this collection?

Rifat Chadirji’s collection also contains photographs by his father, Kamil Chadirji (1897-1968). Kamil Chadirji’s picturesque photography is different in style from that of his son, and therefore adds another historical layer or even a precedent to Rifat Chadirji’s vernacular images. The archive was first housed at the Rifat Chadirji Foundation, a collection of diverse materials assembled and administered by Chadirji himself, which has remained intact while travelling between the architect’s different office locations and later, different home institutions. From the Chadirji Foundation the archive was then housed on a long-term loan at the Arab Image Foundation in Beirut. In 2016 it was relocated to the Aga Khan Documentation Center (AKCD) at MIT. The format and the thematic arrangement of this collection has remained unchanged.

When approaching Chadirji’s archive, we can distinguish between different modes of circulation that it has undergone. One is the internal circulation and organization of print images, contact sheets, folders, to mention a few, that has remained intact; the other is the circulation of the archive between different sites, institutions, and continents; and finally, there is the ongoing digitization of the collection that has created another mode of visibility and circulation of the collection’s content. Each of these modes of circulation, accumulation, and exchange has added a new layer to the archive that should be investigated. My focus was on the first aspect: for me the observation of the traces of how the archive and the images actively worked for Chadirji himself was one of the most rewarding dimensions of working on the printed photographs and binders. Different brightly colored circular tags on the folders’ sleeves, or notes and labels on the verso of the photographs, the missing prints and sheets in the binders, and the thematic labels on each folder speak for ways in which Chadirji configured and reshuffled the internal organization of his archive. He used these photographs either to illustrate his own books or to support his arguments in his design theory and practice.

The challenge is of course the archive’s immensity. As I corresponded with Clémence Cottard, the head of collections at AIF, she judiciously mentioned several dissertations could be written on this archive. The incredible catalogue that AIF published on Chadirji’s archive, Rifat Chadirji: Building Index (2018) contained only reproductions of the contact sheets and photographs of Chadirji’s architecture projects, and we are talking about a 400-page catalogue. In order to navigate my way through the archive I ended up making a mini archive of my own. I did not work on the images of Chadirji’s architecture and design. Instead, I focused on his photographs of everyday life. When I was working through the binders of printed photographs, even the sequence of the images in each folder was intriguing to me. I took pictures of the photographs in the binders’ sleeves and wrote down a visual analysis of each and my understanding of why the images would correspond to the category assigned to them. Although I was closely following Chadirji’s own logic of organization, I inevitably had to intervene and create a new mode of circulation for the images in order to approach them.

3. Your research recovers significant connections between Chadirji’s photographic and architectural practice. How did you approach your analysis of this relationship?

Rifat Chadirji’s archive consisted of two main types of photographs. One comprised the photographs of his architectural projects, and the other, the images of people and everyday life. My focus was on the latter. I initially approached his photographs of daily Iraqi life from a pretty conventional angle. Because a large number of the photographs in Chadirji’s collection documented his architectural projects–namely, frontal elevations and interiors of his buildings– I used the architectural lens as a starting point to make sense of his photographs of everyday life. I first relied on the preservationist perspective, a vein of photography that articulates the interwoven histories of architectural preservation and photography. Practiced from the 19th century onwards, preservationist photography attempted to capture old neighborhoods and buildings before their destruction during intense periods of urban renewals and social transformations. The preservationist approach, as far as my research revealed, was dominated by a dualistic understanding of the relationship between the built environment and people to the point that peopleless images would constitute a major trope of such practices. In this dualistic understanding, people and the spatial structure were configured as separate entities.

But what stood out to me in Chadirji’s images of everyday life was the intense interaction between people and their surrounding built environment. Nevertheless, I was still stuck with the preservationist approach, interpreting the images as a lament and an anxious gesture that aimed to capture the vanishing fabric of traditional Iraqi life and everyday professions in the face of the processes of modernization. Until one day in January 2019, while strolling in the Art Institute of Chicago, I saw Naeem Mohaiemen’s Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017). Focusing mostly on the mid 1950s through the 1970s, Mohaiemen’s three channel film installation recounted the story of an ambition: the ambition to unify the post-colonial space of the global south against bipolar perception of the Cold-War world. Mohaeimen used abandoned monumental architecture as one of his key metaphors to decipher this moment and its lost legacy– the faith in the unified space of future, the faith to create a better future. The film deeply impacted my understanding of Chadirji’s project. Chadirji, too, belonged to a generation of cultural arbiters who aimed to transform and reconfigure the order of the world. But that generation’s undertaking, as the film depicted, was not simply a reaction, it was more of an active remedial response tied to a sense of care. Thus, the film, even though on a subject entirely different from Chadirji’s photographs, allowed me to shift my frame of reference from reaction to responsiveness. Responsiveness allows for articulating a co-constitutive relationship among agents. Revisiting the images through this lens of responsibility and responsiveness, while engaging with Chadirji’s writings on architecture, I could better see that the photographs were not supposed to produce reified images of bygone spatial configurations and everyday practices.

Instead, as I came to understand, the photographs depicted the interface between people, the built environment and the architect himself. They recounted the way these agents participated in the production of those photographs alongside the production of space. As a result, the diagnostic dimension of Chadirji’s images became more evident to me. One needs to first identify the nature of a phenomenon, distinguish its signs, and anticipate its future course to find the right treatment. Important here is to note that people and traditional spaces of life were not carrying the symptoms of an illness, but the contemporaneous Iraqi architecture was. Chadirji actively returned to the people and their everyday spatial practices for a remedy and critique to modern Iraqi architecture. These photographs depict how people take possession of the space.

4. Tell us about your methodologies, and how you situate your work within the field of modern and contemporary Arab art?

Responding to the question of methodology is easier than situating my work within the field. I try to integrate the two in my response. Writing about Chadirji’s photographs of everyday life could be tricky. We are dealing with an archive that is governed with a clear set of decisions excluding those spaces of everyday life that are not associated with traditional modes of production; we don’t see pictures of factories and assembly lines for instance. One could fall into the trap of interpreting the images through the quasi-critical lens of the self-colonizing gaze of a privileged technocrat directing his objectifying camera from the upper echelons of society towards the bottom. This kind of interpretation actually obfuscates the agency of Iraqi people and would foreclose any chance for the discussion of the relationship between the architect and the people that was so central in Chadirji’s thinking and writing. As I mentioned earlier the preservationist perspective was also another possibility that I moved past. At the heart of both the preservationist and the aforementioned approach lies a kind of Cartesian division that makes a sharp distinction between the observer and the observed, and by extension between the so-called traditional modes of being and the modern ones.

What Chadirji’s photographs reveal is quite the opposite: he offers a relational field of active negotiations between different agents. This relational field contains the relative map of social interactions between the architect and the people, and it does acknowledge differences in social placement but is not limited to that. In fact, these differences are to be bridged and reconciled through establishing a rapport between the architect and the people, which, as I tried to argue, was the raison d’être of his photographic practice. For me, the two mediums of space and photography that Chadirji worked with encompassed this relational site between people, the architect, and space. In fact, both photography and space are mediums that index the presence of not only the people and the built environment, but also the photographer and the architect. Additionally, space and photography comprise plenitude, and this is precisely what Chadirji took advantage of in his images of Iraqi people’s spatial practices. For example, his tilted frames do not communicate an intention to control the pro-filmic event; they rather aimed to capture as much of the unfolding plenitude in front of the camera as they possibly could. The contingency of what came to be captured through Chadirji’s frame corroborates the diagnostic dimension of his practice. As such for me, visual analysis of photographs and close study of the photographic event became pivotal in approaching Chadirji’s project.

Simultaneously, Chadirji’s own writing about the philosophy and teaching of architecture were critical in my understanding of his images. Parallel to these, I used theories of space, and above all Henri Lefebvre’s triad of perceived, conceived and lived space, to unpack the relationship between Chadirji’s work as an architect and urban planner, and his photographs of daily life, without establishing a top to bottom, hierarchical relationship. I understood Chadirji’s photographs as the lived spaces of the encounter between the architect and the people, which allowed Chadirji’s conceptions of space in his design and urban planning to meet the practical test of the material arena of everyday life, or the perceived space. Moreover, these lived spaces are configured by bodies and the way they appropriate their surrounding places to make it work for them. To better grasp the terms of the encounter between Chadirji and people, I turned to social art history and illuminating readings on Iraq’s modern history and urban planning.

Here is perhaps a good place to situate my research on Chadirji’s archive within the field of modern and contemporary Arab art. Working on Chadirji inevitably demands a multi-scalar analysis that is embedded in the region and Arab culture, while simultaneously moving beyond it. Rifat Chadirji is an architect and theorist who questions the mechanistic and widespread international cliches of Modernism, while rejecting conventional building technologies and fragmented ‘quotations’ from Iraqi traditional architecture. I think any research involving Chadirji would inevitably bring together the place-bound and the worldly dimension of modern art theory and practice. Chadirji’s work bends the crude dichotomy between modern and traditional, local and global, observer and the observed, and between people and the architect. His practice generates epistemologies for better understanding Iraqi modern art, culture and social thought that is not developed in isolation from the broader world-space negotiations. Similar to a number of his fellow Iraqi, Lebanese, and Egyptian artists and literary figures of that time, Chadirji aimed to conceive a framework capable of articulating not only the particular but also the broader human experience. In his writings, he emphasized the relationship between human social needs and the corresponding technology and knowledge that would fulfill those needs. Chadirji foregrounded the place of everyday experience in the production of architectural knowledge and artifacts, while simultaneously mobilizing conventions and technologies embedded in Iraqi tradition as well as modern traditions of design and building. While I think the epistemologies that Chadirji configured in his work constitute an important contribution to the unique discourse of Arab modern art and architecture, I think his work enhances the broader discourse of global modernisms. I hope my paper on Chadirji, too, could be as much embedded in the unique history of Arab modern art as is in the broader context of modernisms

5. How does your research build on or differ from other studies of modern and contemporary photography in Iraq or elsewhere?

As I approached Chadirji’s photographs, the first step was to better see the images and comprehend the photographic event. In doing so, I had to draw on numerous studies on photography. For instance, Christopher Pinney’s writing on photography and print materials in India were revelatory and helped me rethink the pro-filmic event in Chadirji’s images and the agency of people who populated them. Likewise, I benefited from Elizabeth Edwards and Deborah Poole’s critical analysis of anthropological and colonial archives to appreciate Chadirji’s deliberate inclusion of plenitude in his frames while photographing Iraqi practices of everyday life. Additionally, Ariella Azullay’s writing helped to shift my attention from the photograph as a record of an event to the event of photography as a field of encounters between different protagonists. This understanding aligned with the writings of Chadirji and the pivotal relationship between the architect and the people in his work.

The second step for me was to contextualize Chadirji’s practice. In order to make sense of Chadirji’s vernacular photography, I situated his collection in relation to two types of contemporaneous photographic practices, each of which also documented the everyday, albeit through disparate lenses. The first one I called “the beautification mode,” through which I suggested the genre of representation practiced by several Iraqi photographers, primarily by Latif Al Ani, the father of Iraqi photography. In his photographs of everyday life Al Ani revered and beautified the depicted subject through specific aesthetic and thematic choices. The other type constituted the vernacular photographic projects undertaken by a number of European-trained architects, above all by CIAM architects (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne), which focused on the daily life of ordinary people. I argued that Chadirji’s photographs were “diagnostic,” and therefore different from these other projects. I contended that such diagnoses were formed by the interdependent relationship that Chadirji defined with his photographic subjects (the people), and the specific spaces of social life and social production that he chose to depict.

6. How has this project developed over the last few months? Can you tell us more about your current research?

In the past few months my focus has been on the studies of vernacular photography, and also materiality and circulation of images. I dwelled more on writings about photography in ethnography and anthropology to better map out the contours of Chadirji’s project in comparison to such practices. Moreover, I have been thinking about the co-constitutive relationship between the local and global models of spatial configuration as Chadirji aimed to conceive them. Thinking more about Chadirji’s collection, I have been constantly reminding myself that both mediums that he worked with also brought together a generative tension between the fixed and the multi-scalar: space and photography are mediums that cannot be approached in isolation. The lens-based medium’s circulation is facilitated by its reproducibility and its flow through digitized pixels or material prints and negatives. Likewise, space constitutes simultaneously any single unit or any aggregation of bodies, objects, cities, regions, and the globe.

In my current research on modern art in Iran from the 1950s to the 1970s, I investigate the same dynamic: the dialectic of the local and the global. There are many similarities between the creative practice of Chadirji and the Iranian artists that I examine. It always fascinates me how artists from the region, against the high modernist proclamation of distinction between mediums, simultaneously practiced different mediums, and how their multi-media practices constitute their actual oeuvre.

Paper Abstract

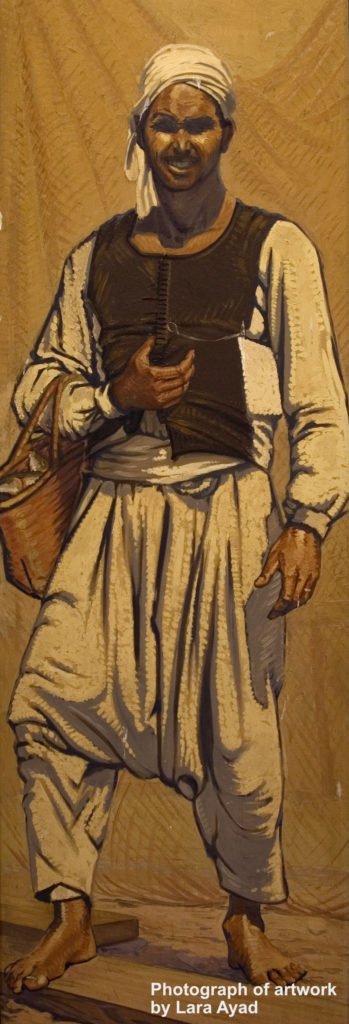

This essay examines a series of four paintings created between 1934 and 1937 by the Egyptian artist Aly Kamel el-Deeb (1909-1997) for the Agricultural Museum. I argue that the male peasant subjects of his painted series, which he left untitled, functioned as heroic members of the Egyptian national community. Central to formulating the image of a national community in Egypt between the World Wars were concepts of nation-building and their intimate ties with ideas of masculinity. My essay situates el-Deeb’s untitled series in contemporary debates among nationalists and artists about the role of peasant men in achieving Egyptian economic and cultural independence, as well as portrayals of rural men as politically potent and culturally authentic figures seen in the works of the local avant-garde and international artists. I demonstrate that el-Deeb re-presented male peasants seen in the Agricultural Museum’s photographic displays as patriotic symbols of “great men” who contribute to Egypt’s agricultural development and create national folk arts.

Brief Bio

Lara Ayad is Assistant Professor of Art History at Skidmore College and teaches courses on African art. She received her PhD in the History of Art and Architecture and a Certificate in African Studies at Boston University in 2018. Lara credits her Egyptian-American family for her symbiotic fixations with art and science.

1) Congratulations on receiving the Saad Prize for your paper, “Homegrown Heroes: Peasant Masculinity and Nation-Building in the Paintings of Aly Kamel el-Deeb.” How did you become interested in the work of al-Deeb?

Thank you! My first encounter with Aly al-Deeb’s work was circumstantial and totally unexpected. When I landed in Cairo in September of 2014 to perform my doctoral fieldwork, I was planning to focus on the art collection of the Museum of Modern Egyptian Art there. But the MoMEA directors and staff moved most of the displayed artworks to storage by the time I arrived. Concerns about the security of the museum’s collections also made my requests to access artworks stored in the storage facilities of the museum nil. It was my search for archival documents about other museum art collections in Cairo that led me to visit the Agricultural Museum, and, by extension, to discover its phenomenal fine art collection. Aly al-Deeb’s life-size paintings of peasant men were tucked away in one of the smaller rooms of the palatial Heritage Collection building at the Agricultural Museum, and I photographed them, along with many other artworks on display.

The more I returned to my photographs of al-Deeb’s untitled series, the more intrigued I became with his subjects. There is this wonderful tension between the slightly cheesy and ethnographic feel of his realist-style techniques and his nuanced efforts to define and celebrate peasant men’s agricultural labor, artisanship, and dance practices. This makes al-Deeb one of the first formally-trained artists in Egypt to spotlight Egyptian folk arts as a key element of national cultural heritage. The result of his work at the Agricultural Museum is a powerful and complex portrait of a rising national community that was distinctly Egyptian and male. His four canvases also received many visitors during and after the museum’s inauguration in 1938 because they were originally displayed on the ground floor of one of the most popular exhibition buildings in the massive museum complex – the so-called Animal Kingdom Building.

And, yet, scholars who write about modern Egyptian art in Arabic, English, and French rarely talk about Aly al-Deeb, let alone representations of peasant men. The lack of critical writings about the Agricultural Museum and its art collection motivated me to focus on al-Deeb’s work with even more purpose. With the exception of art historians, such as Nadia Radwan, many scholars and critics have ignored the Agricultural Museum and its fascinating combination of fine art, science, and history displays. I think this is partly because it defies neat divisions that some writers have made between the fine arts and other visual modes of expression and institution-formation in twentieth-century Egypt. Aly al-Deeb’s paintings were part of a much wider exhibition space that put art in the service of science, and vice-a-versa. But they were also crucial for Egyptian government officials who wanted to make Egyptian farming, agricultural heritage, and local products sexy for an Egyptian public that they envisioned as both citizens and consumers.

Looking back, I am glad that the Museum of Modern Art did not work out for me, because it paved the way for a project focused on representations of peasant figures in an exhibition space as old, unique, and eclectic as the Agricultural Museum. And I love just about anything that people have overlooked or neglected because of that thing’s weirdness, because of its ability to challenge our expectations about what constitutes art, and about what art does to shape people’s understanding of their place in the world.

2) Your paper does an incredible job of situating al-Deeb’s work within a broader visual culture in Egypt at the time drawing on illustrations in the press, ethnographic portraits, photography, and al-Deeb’s own fine arts training to unpack the work’s iconography and cultural and political significance. At the same time, you are careful also to contextualize al-Deeb’s deployment of the peasant as a figure of the nation within an international landscape of the 1930s, relating resonances of al-Deeb’s work to the social realism of Diego Riveria and American regionalists such Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton. Can you discuss the importance of this methodology to this particular moment in the history of art in Egypt as well as to the field of modern art in the Arab world?

Al-Deeb, Rivera, and Benton alike were invested in national, as well as global, debates about rural subjects and their relationship with cultural authenticity, modernity, and even anti-colonial resistance. All of these artists framed the male farmer as the key symbolic actor in these heated debates. In this way, my essay exposes the patriarchal history of cultural populism and folk-art revival on local and international levels.

Al-Deeb’s ability to address national concerns about the role of peasant men in Egypt’s political landscape, as well as global debates about the male rural subject, has major implications for the history of art in modern Egypt. Many scholars have mapped out the relationship between Egyptian modern art, gender, and nationalism in one of two main ways: one scholarly narrative frames art production in national institutions and the avant-garde as inherently distinct and opposed; the other focuses solely on representations of women and the works of women artists. I will address the second pattern of analysis in answering the next question, but the first narrative is especially relevant here and now because there has been a flurry of exhibitions and publications about the Egyptian avant-garde of the 1930s and 40s over the past several years. Sam Bardaouil published his book about Surrealism in Egypt, and exhibitions held in Paris and Cairo have provided valuable analyses and archival information about the avant-garde Group of Art and Freedom. However, these programs and writings have sometimes drawn neat binaries between officially-sponsored and avant-garde artistic practices.

Al-Deeb’s artistic career and his paintings of peasant men reveal profound ideological synergies between the state and the avant-garde, particularly when it comes to issues of gender, cultural authenticity, and anti-colonial thought. His Agricultural Museum paintings, at first glance, seem to portray peasant men as anonymous regional types. Yet, their monumental size, abstracted backgrounds, and affinities with portraits of male politicians elevated these rural figures to the status of national heroes – ones that could save Egypt from Western cultural and economic repression through folk art practices and agricultural labor associated specifically with rural men. What’s fascinating is that al-Deeb began creating murals, paintings, and displays at national museums in Cairo shortly after creating illustrations in 1935 for the anti-establishment publications of Les Essayistes, who were headed by Georges Henein and served as a critical precursor to the more famous Art and Freedom group. Government ministers and members of the avant-garde alike were celebrating Egyptian peasant men’s artisanal skills and manual work, and they all understood these rural figures as the protagonists of Egypt’s transformation into a country that was culturally authentic, industrious, and economically independent.

Analyzing al-Deeb’s paintings of peasant men in both the Agricultural Museum context and international developments helps break down the East/West binary that, I think, persists in many written histories of modern Arab art. We are starting to move away from the traditional preoccupation we’ve had with “Are these Arab artists mimicking or resisting Western influence?” But we still have some work to do, and, because of my training in African art, I’ve found that scholars specializing in modern and contemporary African art have given all of us art historians and art critics incredibly useful frameworks for surpassing West vs. the Rest dichotomies, as well as the attendant questions of mimicry that plagued the study of African art years ago. Fleshing out the local significance of al-Deeb’s paintings in conversation with their role in Mexican and American expressions of culturally authentic manhood shows that modern Arab art often defies simple accusations of mimicry or resistance vis-à-vis “the West.”

3) Gender is an important lens in your analysis. How does your work intervene in previous studies on gender and nation-building?

I think just about every book I have read on gender and nation-building in Egypt or the Middle East focuses solely on women as subjects of analysis. The only exceptions to this are a few historical sources concerned with the formation of modern masculinities in Egypt. Wilson Chacko Jacob’s book, Working Out Egypt, and Lucie Ryzova’s examinations of the effendiyaand their cultural formation accomplish this well. There is also an important anthology on manhood in the Middle East called Imagined Masculinities, edited by Mai Ghoussoub and Emma Sinclair-Webb. Besides that, many of us scholars are guilty of swapping “women” and “gender” in our writings, and in our more casual conversations with each other about research. It makes sense that we have given more attention to women and their roles in history, politics, and art over the past few decades because general histories of the world have traditionally focused on men, and many of us are trying to challenge patriarchal writings of history. I, too, analyze representations of women in my other research projects, which stem mostly from my doctoral dissertation.

Nevertheless, I believe that making women invisible erases their contributions to our world, while making men invisible actually protects them and the pervasive nature of male dominance in most, if not all, aspects of life worldwide. I’ve stated before that the male experience, and nationalist models of masculinity, formed the backbone of populist cultural movements and regionalist practices around the globe during the period between the World Wars. And, yet, the books and articles that I pored through for information on Egyptian painting, sculpture, popular culture, and cinema rarely discussed male figures as gendered subjects. Al-Deeb created his four paintings of peasant men at a time when many countries, including Egypt, were suffering from the global economic depression, facing the dawn of yet another world war, and witnessing the deterioration of European colonial control in the so-called global South. The specter of the male body became increasingly important at this tumultuous time for symbolizing a member of a national collective that could compete on the world stage and surpass the debilitating effects of drastic economic and political change. This stood in stark contrast with artistic representations of peasant women, who often served as allegories of a country’s cultural condition or natural beauty. My hope is that my research will help people understand masculinity as something that is, and always has been, dynamic and culturally contingent, rather than “natural,” rigid, and inherently stable. A more critical lens on manhood also challenges the popular misconception that men have always navigated the world as an ungendered “standard” of human experience, against which women must always be compared.

4) One of the oft-noted commentaries in our field is the absence of centralized and/or public archives. What are the archives you mobilized in this study?

Centralized, public archives are definitely difficult to find or access in many parts of the world, but especially in Egypt right now. According to the Agricultural Museum staff, whom I talked to in 2015, the museum has no institutional papers. I am not sure how true this is, but, when digging through the museum’s own on-site library, I did have a hard time finding any books, newspaper articles, or documents with information about the founding or curation of the Agricultural Museum. The library has some excellent early twentieth-century texts on the sciences – botany, zoology – and an original copy of Description de l’Egyptethat gave some helpful clues about the motivations and education of the museum’s first directors. These men included a set of Hungarians and an Egyptian horticulturalist by the name of Muhammad Zulficar.

As I learned more about the Agricultural Museum’s affinities and shared history with other national museums of art, agriculture, science, and history, I started meeting with the directors of the Mahmoud Mokhtar Museum and the Ethnographic Museum at the National Geographic Society. The latter has a phenomenal collection of books and illustrations on the social and “hard” sciences, history, and civilization gleaned from Muhammad ‘Ali’s and the Khedive Ismail’s personal libraries.

Of course, I turned to the National Archives in Cairo, but I was only given access to the files of the Abdeen Palace, and then with additional restrictions. The MoMEA’s fabled art library, first formed by the artist Ragheb Ayad, was not an option. So, I turned to any information available at the National Archives on the School of Fine Arts, and I also looked to cultural magazine and monograph publications by and about modern Egyptian artists, located at the Dar al-Kotob section of the National Archives. Periodical features on the sciences there proved very useful, as they gave me some context for the subjects of display at the Agricultural Museum, and shed light on how important scientific study was to Egyptian nationalists at the time.

Newspapers served me well, because, as I was poring through issues of al-Ahram, al-Musawar, and other periodicals for features on the museum itself, and on agricultural-industrial expositions and fine art exhibitions, I also found fascinating advertisements. These soap and cosmetics ads portrayed all sorts of illustrated characters that helped me ground al-Deeb’s paintings in popular perceptions, as well as institutional narratives, of gender roles, racial identity, and nationhood in early twentieth-century Egypt. The Rare Books Collection at the American University in Cairo was a great source for postcard photographs of the Egyptian countryside and peasants from this period, as well as exhibition catalogues and personal literary collections of famed Egyptian cultural figures, such as the painter Salah Taher and the architect Hassan Fathy. I’ll add that the Netherlands-Flemish Cultural Institute in Cairo was a cheerful, welcoming space with well-preserved and highly accessible issues of al-Musawar– one of the only newspapers I have ever found that featured the inauguration of the Agricultural Museum in the 1930s.

I also accessed Arabic-language books with in-depth artist biographies and art criticism anthologies from people’s personal collections, particularly those of Hisham Ahmad at the Gezira Arts Center, Mostafa al-Razzaz from the Faculty of Fine Arts, Helwan, and contemporary artists Khaled Hafez, Yasser Mongy, Mohamed ‘Abla, and ‘Ezz al-Din Naguib. ‘Abla also founded a museum of Egyptian caricature in Fayoum, where you can find a small library with earlier periodicals about the folk arts, and books for purchase on the history of political cartoons and caricature in Egypt. Such sources are a fantastic avenue for examining the relationship between popular and fine arts relevant to my study of peasant men subjects. International sources came from the digitized collections found on France’s National Library website, as well as the Harvard Libraries, the latter of which often had more comprehensive and better-preserved collections of early twentieth-century Egyptian texts. All of this being said, if you want to access a centralized archive for modern Egyptian art and visual culture, you have to create it through movement in the city, travel outside of it, and, of course, through meetings with many people – both planned and impromptu.

5) What are some of the challenges and possibilities defining the study of modern art in the Arab world and Africa today?

The fields of modern African and modern Arab art today often deal with the same artists and artworks, if not the same regions of the world – many people living in Africa, and indigenous to the continent, speak Arabic as a primary language. So, historians of modern art from the African continent and other Arabic-speaking regions of the world are often dealing with the same challenges. I think the most significant challenge facing us today is dealing with the canon of art. It’s not just the canon of art made by and for western Europe and the United States that we have had to reckon with. We’re also increasingly having to confront canons of African and Arab art, respectively. Scholars, art critics, and artists from postcolonial nations in Africa and the Middle East have played a significant role in forming these latter canons. But scholars in many parts of the world want to put a spotlight on artists coming from Africa and the Arabic-speaking world because the Western canon of art has marginalized these figures. Yet, in the process of determining which artists are important to examine and learn about, you inevitably have to determine which ones are not so important. Who decides what is important? And how? Should we, as scholars and educators in higher learning institutions, base the subjects of our analyses on particular topics or issues? Time periods? Mediums? Styles?

The formation, and disintegration, of a canon of African art has come to mind, especially now, because I teach surveys of African art based on a textbook that has been out of print for years. Several of the scholars that pioneered the study of African art in its own right during the 1960s, 70s, and 80s are passing away, and there seems to be a vacuum in publications that help create guidelines for some type of canon, a guiding framework for a survey, of African art. While the traditional canon of “classical” African art focused disproportionately on sculptural works made by men without formal art training during the 19thand early 20thcenturies, primarily in rural areas of West and Central Africa, scholars of African art active over the past twenty to thirty years have been disrupting the canon. Studies of formally trained artists from Africa and the African Diaspora working in painting, multimedia installation, sculpture, and video are helping achieve this, and they are also dispelling the myth of the “ethnographic present” that sometimes created the allure of ritual, male-made artworks that drew in earlier generations of scholars. However, the downside of this development is that studies of modern African art are starting to entirely replace critical studies of the “classical” African art I mentioned before. I think we need to find some way to bridge the two camps of African art history so that we and our students can benefit from learning about African artistic production in its particular sociohistorical and cultural contexts.

The field of modern Arab art is a bit newer than that of African art, both in the U.S. and worldwide, which has an impact on determining whether there is even a canon of modern Arab art to begin with. There is certainly a canon of modern Egyptian art, particularly in the Arabic-language literature on the topic! However, I’ve noticed one or two patterns in the wider field of modern Arab art. One of the most upsetting has been the tendency of many scholars and art dealers to interchange modern Arab art with “modern Islamic art.” There is nothing inherently “Christian” about the work of, say, Andy Warhol or Pablo Picasso, so why should there be anything “Islamic” about the works of artists who identify as Arab, or who come from Arabic-speaking, or even Muslim-majority, countries? Furthermore, even when dealing with religious and spiritual themes apparent in works of art from these regions, it is important to consider that sizeable numbers of Arabic-speakers are Christians, many of whom make art themselves. I am not denying that Islam has had a major impact on many realms of life, and, in some cases, art-making. But, our fixation in the English- and French-speaking worlds on Islam as a style or defining characteristic of modern Arab art comes from our obsession with the Other in the art world, the latter of which is based on western European and American understandings of Christianity, secularism, identity, and politics. If we want to make exhibitions and publications that enrich our understanding of modern Arab art, we should think a little bigger, a little more creatively, than high-definition images of exotic Arab women with veils and “Islamic” calligraphy.

Possibilities for the studies of modern African and Arab art moving forward come to life when we put the two fields in direct conversation: how can we mobilize the methods of one field to open conceptual horizons for the other? Translated anthologies of key artist and art critical writings, such as Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, provide a great model for similar books on modern African art – many of its creators’ writings and manifestos, and the essays of African modern art critics, have yet to be published in accessible and collective form. Scholars of modern Arab art, in turn, have much to learn from those specialized in modern African art, particularly when it comes to questions of racial representation, diasporic experience, and the power of contemporary art exhibitions to represent and marginalize artist voices, and to form new art canons.

6) Can you share a little about your current research projects?Right now, I am developing my writing and research on Aly al-Deeb’s paintings of peasant men and masculinity from my dissertation and converting it into a journal article. Representations of the Sudanese and East Africans in modern Egyptian painting from the Agricultural Museum have been the main topic of a concurrent study, which I plan to develop and publish as another peer-reviewed article in the next year or so. This second project is exciting because, in it, I deal with the very question of Egypt’s racial and cultural identity vis-à-vis its home continent of Africa: is Egypt “African” or “Mediterranean”? How did Egypt’s colonial history in the Sudan impact artistic representations of the Sudanese? And what does that have to do with Africa? What I’ve found is that artworks created for the Agricultural Museum’s original Sudan section played a major role in distancing Egyptians and their modernity from the supposedly primitive condition of the Sudan, the latter of which, to many Egyptians, represented an African frontier. Gender roles played just as prominent of a role in paintings and sculptures of Sudanese and East African subjects as they did for their Egyptian counterparts found in other parts of the museum. My upcoming publications take an intersectional approach to examining the place of Sudanese male and female subjects in Egyptian nationalist models of manhood and femininity, respectively. In fact, paintings of Sudanese warriors were the antithesis to the ideal masculinity and citizenship we see represented in al-Deeb’s visual ode to heroic Egyptian peasant men. Stay tuned!